Well, they can eat sh*te! I’m not joking. When someone says you’re “too much” it depends on so much but little of it has to do with you. If you spent any time lamenting on their words, the tone, the interpretation, instead of just asking them to explain it would drive you mad. Growing up in predominantly white spaces and learning about human behavior from a Western cultural perspective, can really make one entirely unaware that one person’s “too much” is another person’s “perfect”. Understanding the subtext behind this comment requires unpacking emotional norms, interpersonal dynamics, and the implicit biases that shape perceptions of emotional expression and emotional overreaction.

What is “Too Much” Emotionally?

The phrase “too much” is inherently subjective; it doesn’t measure your emotions against some universal standard, but rather reflects a personal judgment made by the person experiencing your emotional expression (Immordino-Yang et al., 2017). What they’re often reacting to isn’t the emotion itself, but a mismatch between their own comfort level or emotional bandwidth and the way you’re expressing yourself.

For example, someone who values emotional restraint may feel uncomfortable when faced with tears, excitement, or anger expressed openly not because those emotions are inappropriate, but because they exceed what they consider normal, manageable, or acceptable. In that moment, your expression is too much for them, not necessarily too much in any objective sense.

Common Interpretations Include:

- Emotional intensity: Strong feelings that are expressed openly, such as crying, anger, or exuberance.

- High reactivity: Quickly shifting moods or strong reactions to stimuli that others may view as minor.

- Persistent expression: Continual sharing or processing of feelings, especially in social contexts.

- Perceived dependency: Seeking reassurance, validation, or emotional closeness more frequently than others are comfortable with.

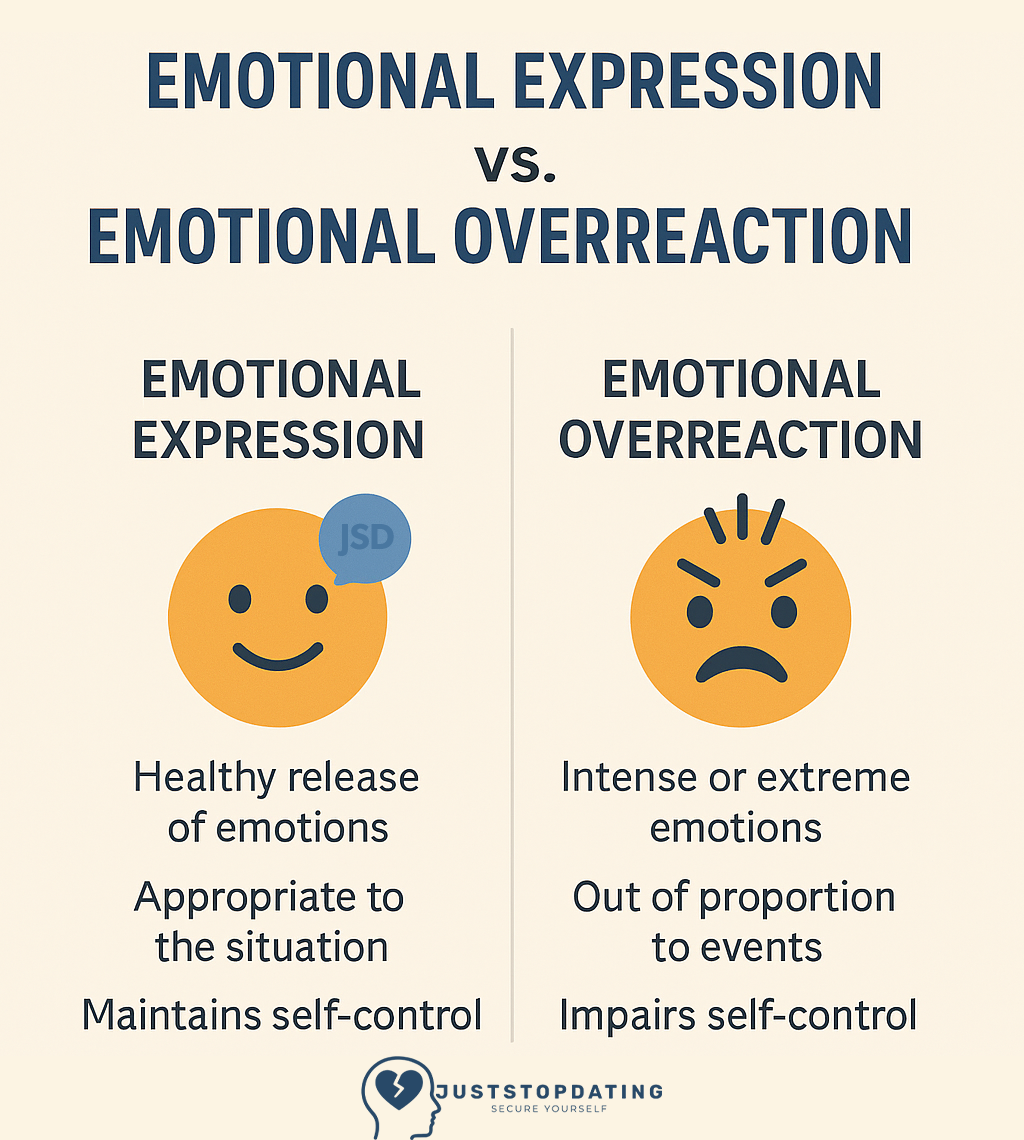

Emotional Expression vs. Emotional Overreaction

Before labeling someone as “too much,” it’s essential to distinguish between emotional expression and emotional overreaction, two concepts that are often blurred, especially across cultural or relational differences. One is a healthy, human way of communicating; the other is typically a value judgment that depends heavily on context, bias, and personal tolerance.

What one person sees as honest expression, another might perceive as excessive but that difference is often rooted not in emotional pathology, but in clashing emotional norms. Understanding the difference requires asking: Is the emotional response actually disproportionate or dysregulated, or just unfamiliar or uncomfortable to me?

Emotional Expression

This refers to the outward display of internal feelings, such as through:

- Verbal: “I’m hurt you didn’t call me back.”

- Non-verbal: Crying, facial expressions, tone of voice, body posture.

- Behavioral: Withdrawing, lashing out, texting repeatedly, pacing.

Emotional expression is context-dependent, influenced by personality, culture, gender, and relational norms. It is not inherently negative in fact, it’s a key part of how humans connect, regulate emotions, and make meaning in relationships.

Emotional Overreaction

This term is usually a subjective judgment made by someone who perceives another’s emotional response as too intense or disruptive. It typically implies:

- A disproportion between the situation and the emotional response.

- A perceived loss of regulation, such as yelling or shutting down over something minor.

- A pattern of escalation that begins to harm communication, relationships, or functioning.

The key question is often framed as: “Would a reasonable person view this emotional response as appropriate in this context?” But that idea of “reasonable” is not neutral; it’s culturally constructed, class-bound, and often racially or gender biased. What’s seen as overreacting in one environment may be completely normative or even necessary in another.

Cultural Norms Determine Emotional Limits

Emotional norms vary drastically across communities, and reactions that are seen as excessive or pathological in one group may be entirely healthy, expected, or even valued in another. In many white, professional-class Western contexts especially in male-dominated or academic spaces stoicism and emotional restraint are idealized. Emotional control is equated with rationality, strength, and competence. Conversely, visible emotion (joy, sadness, anger) is often pathologized or dismissed as immature or unprofessional.

But those values are not neutral; they are class-bound and culturally specific. In working-class communities, many Black and Brown cultures, and collectivist societies across Africa, Latin America, and South Asia, emotional expressiveness is a form of connection, care, and truth-telling. It’s part of the communal fabric. To restrain joy, grief, or outrage may actually signal detachment or dishonesty.

Even responses often viewed as “overreactions” , intense crying, yelling, passionate displays are not inherently dysregulated. In some cultures, they are signs of sincerity, vitality, or respect for the gravity of a situation. In others, emotional understatement can be read as aloof or even hostile.

So, when someone is told they’re “too much,” it’s often about crossing an invisible boundary of someone else’s cultural comfort zone. If you’re from a culture where stifled emotional responses are the norm, let’s walk through examples of how people celebrate. If you’re joyful beyond measure, learn about how some people keep their excitement to a mere smile and not more than that.

Scenario: Someone Gets a Job Promotion

A person receives great news they’ve just been promoted at work after months of effort. The promotion comes with a pay raise, a new title, and public recognition from management. They walk into a room with friends, family, or coworkers and share the news.

What happens next and how people around them react varies dramatically across cultural and class contexts. These reactions aren’t just personal quirks; they reflect deeply ingrained cultural values about emotion, community, and status.

| Culture/Region | Typical Emotional Response | Social Interpretation |

| Black American culture | Vocal and embodied: hugs, clapping, outward praise, dancing, storytelling, calling extended family. Church, hair salons, barber shops often amplify this. | Joy is communal and expressive— it often resists historical erasure and systemic suppression. Mainstream culture frequently labels it as “loud” or “unprofessional” due to racial bias, not excess. |

| China, Japan (East Asia) | More nuanced: public displays might be muted, but in-group (family/friends) expressions can be strong. | Outward restraint = social order and face-saving. But group-based joy is still valued in private. |

| India, Pakistan (South Asia) | Family, friends, even neighbors may show up uninvited to celebrate. Loud blessings, gifts, food, and effusive praise. | Emotional display = sincerity. Restraint can be interpreted as indifference or even envy. |

| Mexico, Brazil (Latin America) | Hugging, enthusiastic praise, emotional outbursts, music, sometimes spontaneous parties. | Emotion = connection. Celebration is a social obligation, not an indulgence. |

| Nigeria, Liberia, Ghana (West Africa) | Loud celebration, clapping, singing, dancing even among coworkers or acquaintances. | Joy is communal. Suppressing emotion is unnatural. Not celebrating with someone is rude or cold. |

| Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland) | Understatement is a virtue. “Lagom” (not too much, not too little). A calm “congrats” might suffice. | Expressive behavior can seem boastful or vulgar. Stoicism = social harmony. |

| White Middle/Upper class (U.K., U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Canada) | Smile, modest nod, perhaps a “that’s great.” Celebratory tone is often low-key. | Emotional restraint = maturity, professionalism. Loud joy can be seen as immature or attention-seeking. |

| White Lower Class (U.K., U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Canada) | Vocal, celebratory: clapping, joking, hugging, shouting “hell yeah!”, Facebook posts. Often includes shared food or drink. | Celebration is authentic, communal, tied to pride and resilience. Emotional display is genuine, not boastful. But may be looked down on as “loud” or “crass” by elite classes. |

Psychological Perspectives

From a psychological standpoint, being labeled “too much” emotionally might correlate with certain personality traits or attachment styles, but it’s not inherently pathological.

- High emotional intensity is linked to traits like high neuroticism, openness, or borderline traits but also to empathy, creativity, and emotional intelligence.

- People with anxious-preoccupied attachment styles may express emotions more intensely or seek closeness more frequently, which some partners or friends might misinterpret as “neediness.”

It’s important to note: emotional expressiveness is not the same as emotional instability. Being emotionally expressive doesn’t necessarily mean someone lacks regulation or awareness.

Why People Say It

When someone says you’re “too much” emotionally, it’s often less about you and more about them. It can reflect:

- Their own discomfort with emotions, especially if they were socialized to suppress them.

- Avoidant attachment patterns, where intimacy feels threatening.

- Boundary confusion, where emotional disclosure feels overwhelming or unwanted.

- A mismatch in emotional communication styles, not an objective flaw in one party.

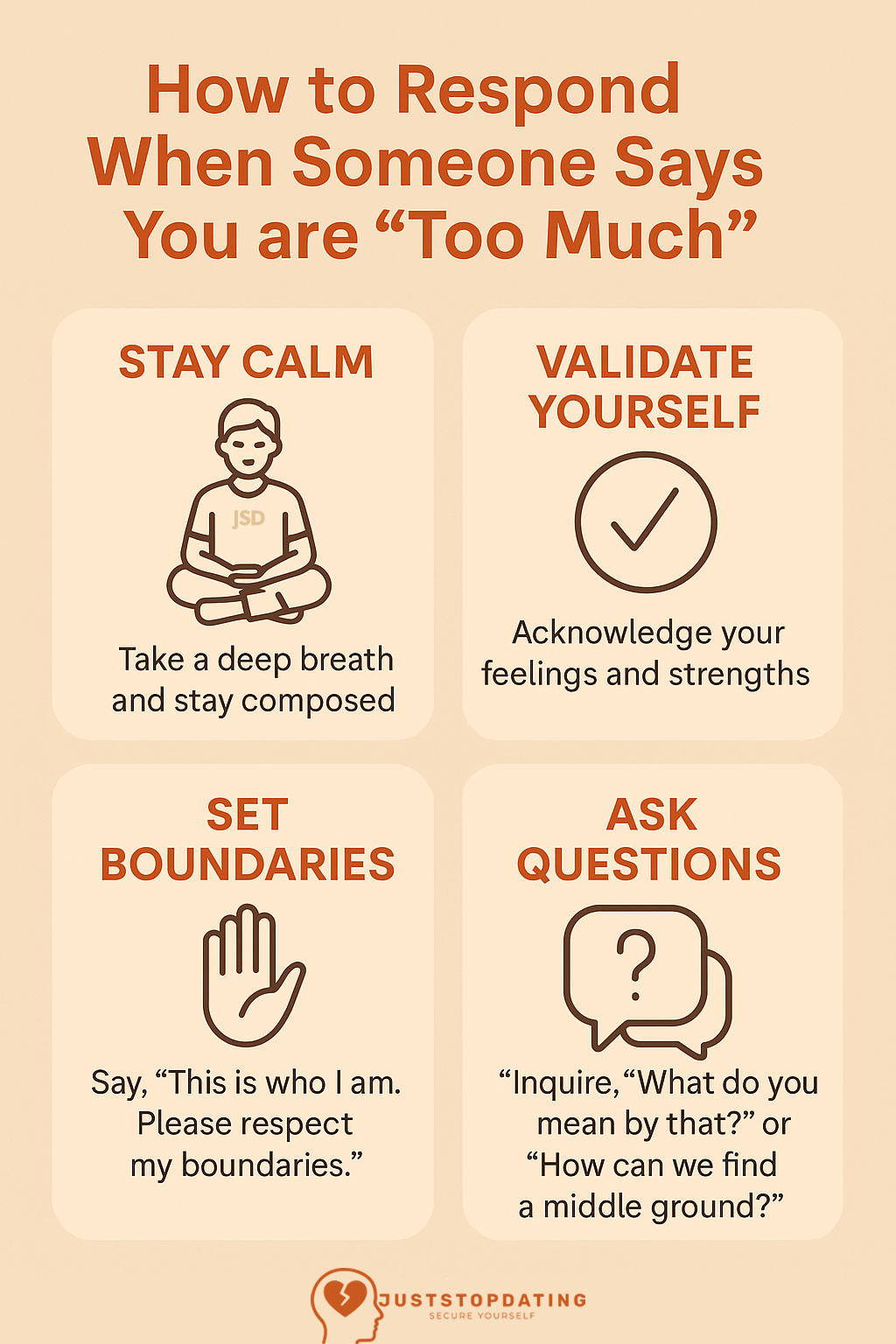

How to Respond When Someone Says You are “Too Much”

Being told you’re “too much” says less about you but more about the other person’s limits, values, or cultural norms than about any objective emotional truth. Here’s how to approach the comment with critical self-awareness and compassion:

1. Reflect on the Context and the Source

Before taking this label to heart, consider who is saying it, and under what circumstances. Is this someone close to you, or someone who may be uncomfortable with emotional expression in general? Could cultural background be playing a role for example, are they from a community that values emotional restraint while yours encourages openness and connection? Psychological frameworks like attachment theory also come into play: people with emotionally avoidant or dismissive tendencies often experience intense emotion as threatening or destabilizing.

Finally, think about power: is this feedback coming from someone in a position of authority or privilege who may be using “too much” to police or silence your emotional expression? Understanding the speaker’s frame can reframe the meaning of the comment entirely.

2. Check in With Your Own Emotional Patterns Without Shame

Self-reflection is valuable but it should be done without collapsing into self-blame. Ask yourself: are there moments when your emotional responses feel overwhelming, even to you? Do you sometimes react impulsively, or project unresolved feelings onto others? Are you seeking emotional connection, or unintentionally overwhelming people with unfiltered emotion?

There’s nothing inherently wrong with feeling deeply the issue, if any, may be in how those feelings are communicated or contained. Emotional intensity is not the same as emotional dysregulation, and many expressive people are also highly self-aware. The goal here is not to suppress your feelings but to notice patterns that might benefit from more regulation or clarity not for the sake of others’ comfort, but for your own stability and agency.

3. Seek Alignment, Not Shrinkage

You are not meant to be emotionally compatible with everyone and that’s not a flaw. Some people are simply not able or willing to meet you at the emotional level you occupy, and that doesn’t make you “too much” any more than it makes them “too little.” The goal isn’t to shrink yourself to fit into relationships that can’t hold you it’s to find relationships where your emotional depth is met with curiosity and care, not defensiveness or disdain.

Emotional alignment isn’t about sameness; it’s about mutual respect. Pay attention to how you feel after expressing your emotions safe and seen, or ashamed and silenced? That’s your compass.

4. If You’re the One Saying “You’re Too Much”…

If you’ve ever told someone they’re “too much,” take a moment to turn the lens inward. What specific emotions or behaviors felt overwhelming to you and why? Were you genuinely setting a boundary, or were you reacting from discomfort with strong emotion? Many people have been conditioned to suppress their own feelings and, as a result, struggle to witness others expressing theirs.

It’s okay to have limits, but it’s important to ask whether your response is about preserving your boundaries or about policing someone else’s emotional style. There’s a big difference between saying, “I need some space to process” and saying, “You’re too much.” One creates room for both people’s needs and the other shuts vulnerability down.

Remember, One Person’s “Too Much” is “Perfect” to Someone Else

The phrase “too much” is a subjective response to a perceived mismatch in emotional style, tolerance, or cultural norm. Before you internalize it, or weaponize it, pause and ask: what is actually being said here, and what isn’t? Emotional expression is not a defect. It’s part of what makes us legible, connective, and human. The challenge is not to be less, but to find or create the spaces where your emotional truth can be honored without distortion.

Rather than seeing emotional depth as a liability, it can be reframed as a strength one that enhances connection, empathy, and authenticity. The challenge lies not in being “less” emotional, but in finding relationships and environments where emotional presence is welcomed, rather than pathologized.