The attachment styles are essentially your brain’s default dating operating system, programmed during your earliest years and stubbornly persistent throughout your romantic life. These attachment bonds each have distinct characteristics that are intimately tied to fundamental aspects of mammalian life, including pregnancy, birth, lactation, and infant brain development. Think of your attachment bonds being some sort of quilt or tapestry that was started while you were a baby. As you age, different memories are sewn on. Some are good, some are just okay memories, and some break your heart. The good thing about a tapestry or quilt is you can start over whenever you want. Sometimes, you’re lucky to find someone who can help you make something special.

Attachment theory, in a sense, was an attempt to develop an approach to understand how the attachment styles functioned as bonds essentially sewn into the quilt of our minds. It was developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth in the mid-20th century, who identified these four patterns that emerged from our earliest caregiver relationships. During World War II and its aftermath, Bowlby began this research on 44 children who were arrested and psychologically evaluated in 1944. Bowlby concluded from the study that parental separation had negatively impacted these children.

The study led Bowlby to further examine the impact of separation in other groups and nonhuman primate species. He concluded that proximity to parental care was important in the formation of attachment bonds (Bowlby, 1973). Since that time, research has shown that in response to distinct infant-caregiver interaction patterns in times of need, infants develop different personality-like dispositions known as attachment patterns. The fascinating part? These patterns remain remarkably consistent from infancy through late adulthood, meaning your dating disasters might be more predictable than you thought.

The Brain Science Behind Attachment Theory

Each of the attachment styles are about how your brain learned to process human connection. Every interaction with your earliest caregivers was teaching your developing brain fundamental lessons: Are people safe? Can I trust them to meet my needs? What happens when I’m vulnerable?

How Your Brain Learns About Love

According to everyone on planet Earth and confirmed by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, infant brains don’t come with manuals for social interactions, instead we learn through relationship that are formed with the people around us. This idea aligns with the concept of brain plasticity, where experiences shape the brain’s wiring and connections.

In the 80s, Bowlby’s attachment research studied key patterns between children and caregivers. When children cried and someone came consistently, your brain built the neural pathways that encoded “relationships are safe and reliable.” When comfort came unpredictably or not at all, different pathways formed ones that might encode “people are unreliable” or “I need to be self-sufficient”. As children, when we learn the attachment styles, it isn’t a conscious process. Each caregiver interaction strengthened these neuronal connections in our brain while others remained weak or underdeveloped.

The Biology of Behavior

The attachment styles operate through specific brain networks that control learning, memory, emotion regulation, and hormone release. The hippocampus helps you remember where you parked your car and also stores implicit memories of how relationships work. The amygdala helps you avoid dangerous situations and it learns to detect relationship threats based on your earliest experiences. When your attachment system activates today, when your partner seems distant these deeply ingrained neural pathways spring into action. Your brain releases specific combinations of hormones like oxytocin, cortisol, and dopamine, each hormone acting as a neurotransmitter binding to neurons in different regions of your brain and controlling how you handle relationship uncertainty.

Why This Matters

Understanding that the attachment styles are neurobiological patterns, not personality flaws, changes everything. Your anxious need for reassurance isn’t weakness, it’s your brain using neural pathways carved by early experiences. Your tendency to withdraw isn’t coldness, it’s an adaptive strategy your nervous system learned for emotional survival. The good news? These neural pathways can be modified throughout life through new experiences, therapy, and conscious awareness. Your brain’s attachment programming was adaptive for your childhood environment, but you can teach it new patterns that serve your adult relationships better.

Secure Attachment

Approximately 60% of U.S. adults are securely attached, the other 40% are likely to fall into other attachment styles: anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, or fearful-avoidant (Stepp et al, 2010). The secure attachment style develops when caregivers consistently respond to a child’s needs with warmth, reliability, and emotional attunement. This creates the foundation for lifelong relationship success.

Ages 0-10: Building Trust and Safety

Early Years (0-5): Securely attached babies cry and someone comes. They’re hungry and fed. They’re scared and receive comfort. This consistency teaches them that people are reliable and that they’re worthy of care. These children explore confidently, knowing their caregiver is always available as a safe home base.

They learn to self-soothe because their caregivers first soothed them. When upset, they seek comfort and are easily calmed. They’re not clingy or overly independent; they’ve learned the perfect balance of connection and autonomy.

School Age (5-10): These kids make friends easily and maintain stable relationships. They can handle being away from parents for school or sleepovers without excessive anxiety. They’re the children who seem emotionally mature for their age they can share, empathize, and resolve conflicts constructively.

Teachers love them because they’re cooperative but not people-pleasing. They ask for help when needed but don’t demand constant attention. They’ve internalized the lesson that relationships are safe spaces for both giving and receiving support.

Ages 10-20: Navigating Social Complexity

Tweens and Early Teens (10-15): Secure preteens handle the social drama of middle school with remarkable resilience. They can maintain friendships through conflicts, aren’t devastated by peer rejection, and don’t need to be popular to feel worthy. They’re starting to develop romantic interests but aren’t desperate for validation.

They can disagree with parents without feeling like the relationship is threatened. They seek independence but don’t rebel destructively; they’ve learned that growing up doesn’t mean losing connection.

Late Teens (15-20): Secure teenagers form their first serious romantic relationships with healthy boundaries. They don’t lose themselves in relationships or avoid intimacy altogether. They can handle breakups without their world falling apart because their sense of self isn’t dependent on their partner’s approval.

They’re preparing for adulthood with confidence, knowing they can maintain close relationships while pursuing their own goals. College transitions are manageable because they’ve learned that distance doesn’t threaten emotional bonds.

Ages 20-30: Launching Into Love

Early Twenties: Secure young adults date with intention rather than desperation. They’re not trying to fill a void or prove their worth through relationships. They can enjoy being single and also embrace partnership when it comes naturally.

They communicate directly about their needs and feelings. When conflicts arise, they don’t shut down or blow up, they problem-solve together. They’re attracted to equally healthy partners because dysfunction doesn’t feel familiar or exciting.

Late Twenties: Many secure adults settle into long-term partnerships during this period. They choose partners based on compatibility and mutual respect rather than drama or intensity. Their relationships are characterized by emotional intimacy, sexual satisfaction, and shared goals.

They maintain individual friendships and interests while building a life together. They handle major life decisions, career changes, moving, finances as a team without losing their individual identities.

Ages 30-40+: Mastering Adult Relationships

The Thirties: Secure adults often become parents and tend to repeat the positive caregiving cycle. They’re attuned to their children’s needs without being helicopter parents. They model healthy relationship dynamics, showing their kids what secure love looks like.

Professionally, they’re often leaders because people trust them. They can give and receive feedback, collaborate effectively, and maintain boundaries without being rigid or defensive.

Midlife and Beyond (40+): Secure attachment pays long-term dividends. These adults have stable marriages with low divorce rates. They navigate midlife transitions, empty nest, career changes, aging parents with emotional balance and mutual support.

They’re often the friends others turn to for advice because they’ve mastered the art of being supportive without being intrusive. They age gracefully, maintaining meaningful relationships and finding purpose beyond themselves.

Their relationships continue growing and deepening rather than becoming stagnant or conflict-ridden. They’ve learned that love isn’t a feeling that comes and goes, it’s a secure bond that can weather life’s inevitable storms.

Secure vs. Insecure Attachment Styles

Before diving into anxious attachment specifically, it’s important to understand what makes attachment “insecure.” Unlike secure attachment, where caregiving was consistent and predictable, insecure attachment styles develop when children’s needs for safety and connection are met inconsistently, inadequately, or in ways that create confusion about relationships.

Insecure attachment isn’t a character flaw, it’s an adaptive response to imperfect caregiving environments. Children with insecure attachment learned different strategies for getting their needs met and protecting themselves emotionally. These strategies made perfect sense in their childhood context but often create challenges in adult relationships.

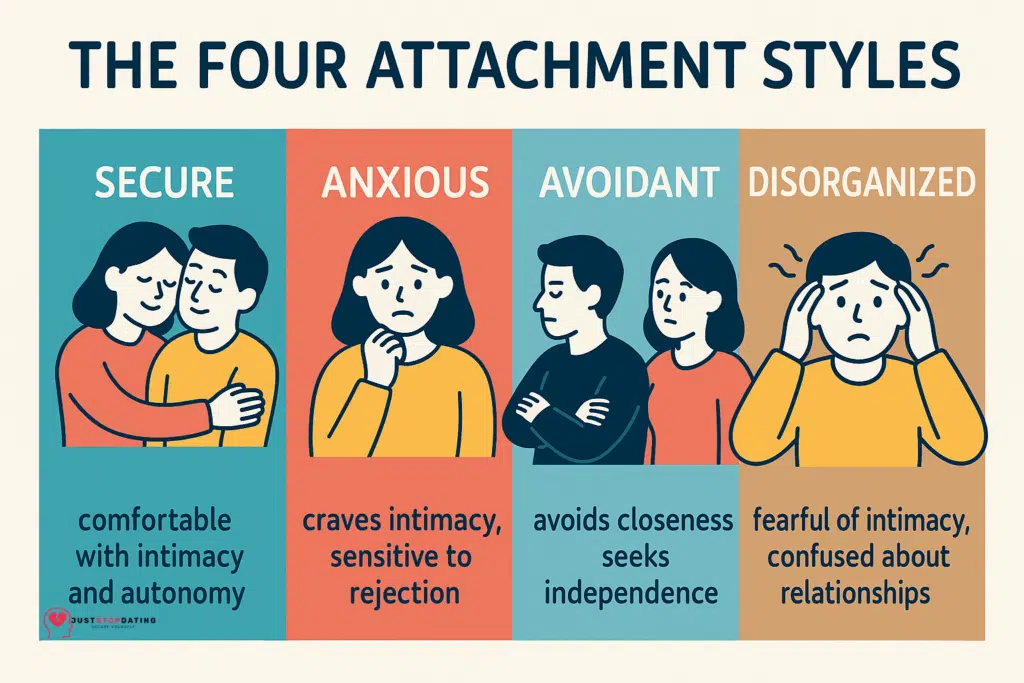

The three types of insecure attachment, anxious, avoidant, and disorganized each represent different solutions to the same fundamental problem: how to get love and safety when it doesn’t come reliably.

Anxious Attachment

About 20% of adults have anxious attachment, also called “preoccupied” attachment. This style develops when caregiving is inconsistent, sometimes warm and responsive, other times distracted, overwhelmed, or emotionally unavailable. Children learn that love is possible but never guaranteed, creating lifelong patterns of hypervigilance in relationships.

The anxious attachment strategy is essentially: “If I monitor constantly for signs of rejection and work hard enough to please people, maybe I can keep them from leaving.” It’s an exhausting but understandable response to unpredictable early relationships.

Ages 0-10: Learning That Love Is Uncertain

Early Years (0-5): Anxiously attached babies experienced caregiving roulette. Sometimes crying brought immediate comfort; other times it was ignored or met with frustration. Their caregivers weren’t deliberately neglectful; they might have been dealing with depression, stress, or their own attachment issues.

These children learned to escalate their distress to get attention. Normal crying didn’t always work, so they developed louder, more persistent protest behaviors. They became hyperattuned to their caregiver’s moods, constantly scanning for signs of availability or withdrawal.

They struggled with exploration because they weren’t confident their safe base would be there when they returned. Instead of playing independently, they often stayed close, checking frequently to make sure their caregiver was still engaged.

School Age (5-10): Anxious children often become people-pleasers or attention-seekers. They learned that being “good” or “special” sometimes earned them the consistent love they craved. They might excel academically or become the class clown anything to secure adult approval.

Friendships were intense but often unstable. They might cling to friends, become jealous easily, or feel devastated by normal childhood conflicts. They interpreted neutral social cues as rejection and needed constant reassurance that they were liked.

Ages 10-20: Intensifying Relationships and Emotional Storms

Tweens and Early Teens (10-15): Middle school is particularly brutal for anxiously attached kids. The natural social upheaval triggers their deepest fears about being excluded or abandoned. They might become dramatic, jealous, or controlling in friendships.

They desperately want to fit in but their intensity often pushes peers away, confirming their fears about being unlovable. They might develop people-pleasing tendencies, saying yes to everything to avoid rejection, or become rebellious to test whether adults will stick around even when they’re difficult.

Early romantic interests become all-consuming. A crush might occupy every waking thought because romantic attention feels like proof of their worth.

Late Teens (15-20): Anxious teenagers throw themselves into relationships with overwhelming intensity. They fall in love quickly and completely, often idealizing partners and moving too fast emotionally. They might have sex earlier than they’re ready for, hoping physical intimacy will create the emotional security they crave.

College or work transitions are especially difficult because they trigger abandonment fears. They might choose schools based on relationships rather than their own goals, or struggle with homesickness that feels unbearable.

Ages 20-30: The Relationship Roller Coaster

Early Twenties: Anxious young adults are often in and out of intense relationships. They attract partners quickly because their enthusiasm and emotional availability can feel intoxicating, but they also overwhelm partners with their neediness.

They analyze every text, conversation, and interaction for hidden meanings. “He took two hours to respond. Is he losing interest?” becomes a constant mental soundtrack. They seek reassurance compulsively but can never quite believe it when it’s given.

They might stay in unhealthy relationships because being with someone who treats them poorly feels more familiar than being alone. Bad attention still feels better than no attention.

Late Twenties: Many anxious adults begin recognizing their patterns during this period. They might seek therapy or start noticing how their relationship anxiety sabotages their happiness. Some begin learning to self-soothe instead of constantly seeking external validation.

However, without intervention, they might settle into relationships with avoidant partners, creating painful pursuit-distance cycles. They unconsciously choose partners who confirm their belief that love must be earned and is always uncertain.

Ages 30-40+: Learning New Patterns or Repeating Old Ones

The Thirties: This decade often brings a choice point for anxiously attached adults. Some continue the exhausting cycle of anxious relationships, possibly becoming anxious parents who inadvertently recreate the inconsistent caregiving they experienced.

Others begin developing “earned security” through therapy, conscious relationships, or corrective experiences with friends or partners. They start learning that their worth isn’t dependent on others’ approval and that healthy relationships involve mutual interdependence, not constant reassurance-seeking.

If they become parents, they might struggle with their own children’s independence, unconsciously needing their kids to need them to feel valuable.

Midlife and Beyond (40+): Anxiously attached adults who haven’t addressed their patterns often experience increasing relationship difficulties. Their constant need for reassurance becomes more burdensome to partners over time.

However, those who’ve developed self-awareness can actually become incredibly empathetic partners and friends. Their emotional sensitivity, once a source of pain, becomes a gift when channeled appropriately. They often become the friends who remember birthdays, check in during difficult times, and create deep emotional connections.

Avoidant Attachment

About 15-20% of adults have avoidant attachment, also called “dismissive” attachment (Magai et al., 2001; Ferrajão et al., 2024; Taylor et al., 2024). This style develops when caregivers are consistently emotionally unavailable, rejecting, or uncomfortable with emotions. Unlike the inconsistency that creates anxious attachment, avoidant attachment forms in response to reliable emotional dismissal.

Children learn that their emotional needs will be rejected or minimized, so they develop a powerful survival strategy: emotional self-reliance. The implicit message they internalize is: “Don’t need anyone too much, because needing leads to disappointment. Safety comes from independence.”

The avoidant attachment strategy becomes: “If I don’t get too close or need too much, I can’t be hurt by rejection.” It’s a brilliant adaptation to emotionally unavailable caregiving, but it creates its own challenges in adult relationships.

Ages 0-10: Learning Emotional Self-Reliance

Early Years (0-5): Avoidant babies had caregivers who were present physically but often absent emotionally. Their crying might have been met with efficiency but not warmth, diaper changed, bottle given, but little emotional attunement or comfort. Some caregivers were actively uncomfortable with emotions, shushing tears or saying things like “big boys don’t cry.”

These children learned that emotional expression didn’t bring the comfort they needed, and might even bring rejection or criticism. They developed remarkable self-soothing abilities out of necessity, becoming the babies who rarely cried and seemed precariously independent.

They appeared to explore confidently, but unlike secure children who used their caregiver as a secure base, avoidant children learned to rely primarily on themselves. They didn’t check in for emotional reassurance because they’d learned it wouldn’t be available.

School Age (5-10): Avoidant children often appeared remarkably mature and self-sufficient to teachers and other adults. They didn’t seek help unnecessarily, handled challenges independently, and seemed emotionally stable. Adults often praised them for being “so mature” or “no trouble at all.”

However, they struggled with emotional intimacy in friendships. They might have many acquaintances but few close friends. They learned to deflect emotional conversations with humor or subject changes, and they felt uncomfortable when others shared deep feelings or needed emotional support.

Ages 10-20: Perfecting Emotional Distance

Tweens and Early Teens (10-15): Middle school social intensity often felt overwhelming to avoidant preteens. While other kids were forming intense friendships and dealing with drama, avoidant children preferred more surface-level interactions. They might have been popular because they seemed “cool” and unaffected by typical adolescent emotional chaos.

They began developing what would become lifelong patterns of emotional regulation through achievement, hobbies, or activities rather than relationships. They might excel in individual sports, academics, or creative pursuits that didn’t require emotional vulnerability.

Early romantic interests were often more intellectual than emotional. They might have crushes but felt uncomfortable with the intensity of feeling, preferring to admire from a distance rather than risk the vulnerability of pursuing someone.

Late Teens (15-20): Avoidant teenagers often appeared more mature than their peers because they weren’t caught up in typical adolescent emotional drama. They might have had casual romantic relationships but avoided deep emotional intimacy. Physical intimacy often felt safer than emotional intimacy.

College transitions were often easier for them than for anxious peers because they’d already learned to be emotionally self-reliant. However, they might have struggled with roommate relationships or close friendships that required emotional sharing and vulnerability.

Ages 20-30: Mastering Independence, Struggling with Intimacy

Early Twenties: Avoidant young adults often thrived in the independence of early adulthood. They could handle living alone, building careers, and managing life without feeling lonely or needing constant connection. They might have been attracted to long-distance relationships or partnerships that didn’t require daily emotional intimacy.

Dating often involved a pattern of initial attraction followed by pulling back when things got “too serious” or when partners wanted more emotional closeness. They unconsciously choose partners who needed them more than they needed their partners, maintaining a sense of control and emotional safety.

They might have excelled professionally because they could focus on work without being distracted by relationship drama. However, they often struggled with workplace relationships that required collaboration or emotional intelligence.

Late Twenties: This period often brought the first real challenges to avoidant patterns. Partners began wanting more commitment, deeper intimacy, or emotional availability that felt threatening. Some avoidant adults began recognizing that their independence came at the cost of loneliness, difficulty maintaining relationships, or a sense that something was missing.

Others doubled down on their avoidant strategies, choosing careers or lifestyles that supported their preference for independence. They might have moved frequently, chosen demanding careers, or maintained multiple casual relationships rather than one serious one.

Ages 30-40+: The Intimacy Challenge

The Thirties: This decade often forces avoidant adults to confront their relationship patterns. Friends are getting married, having children, and building deeper partnerships. The freedom and independence that felt liberating in their twenties might start feeling lonely.

If they become parents, avoidant adults often struggle with the intense emotional demands of children. They might provide excellent practical care but feel overwhelmed by their child’s emotional needs. They risk unintentionally recreating the emotionally distant parenting they experienced.

Some avoidant adults begin recognizing their patterns and seeking therapy or consciously working on emotional intimacy. Others might choose partners who are equally independent, creating relationships that work but lack emotional depth.

Midlife and Beyond (40+): Avoidant adults who haven’t addressed their patterns might find themselves increasingly isolated. Their strategy of avoiding intimacy to avoid hurt becomes self-defeating as they miss out on the deep connections that bring meaning to life.

However, those who develop awareness of their patterns can learn to gradually increase emotional intimacy. Their natural self-reliance becomes an asset when balanced with the ability to connect deeply with others. They often become incredibly loyal partners and friends once they learn to trust that emotional intimacy doesn’t have to mean losing themselves.

Disorganized Attachment

Out of all the attachment styles, disorganized or fearful avoidant attachment is the reported attachment style of about 5-10% of American adults. This is probably the most complex attachment style, developing when caregivers are simultaneously the source of comfort and fear. Unlike other insecure styles that have coherent strategies, disorganized attachment represents a breakdown of strategy altogether. I think by the end of this section, you’ll understand why I am a fearful-avoidant neuroscientist.

Children with disorganized attachment face an impossible paradox: they need their caregiver for survival, but that same caregiver is also a source of threat. This might involve abuse, severe neglect, caregivers with untreated mental illness, or parents dealing with their own trauma who are loving one moment and frightening the next. In my case, I am the child of an immigrant from a war-torn country. They didn’t have time to practice breathing exercises or healthy adaptive behaviors.

Their brain shifted away from calm to fight-or-flight or like my dad would say, fighting while flying away. Interestingly, people with fearful-avoidant attachment also tend to excuse the inexcusable and remain in relationships that are emotionally strained. We are the type to forgive, but never forget because we are simultaneously working on an exit strategy from what causes emotional discomfort.

The disorganized attachment response is essentially: “I desperately need you, but you terrify me.” There’s no coherent strategy that can solve this dilemma, leading to chaotic, contradictory behaviors that persist into adulthood.

Ages 0-10: When Safety and Threat Collide

Early Years (0-5): Disorganized babies experienced caregiving that was fundamentally contradictory. The person meant to provide safety was also unpredictable or frightening. This might have involved physical abuse, emotional volatility, substance abuse, or caregivers who were so overwhelmed by their own trauma that they couldn’t provide consistent emotional safety.

These children displayed confused, contradictory behaviors. They might run toward their caregiver when distressed, then suddenly freeze or collapse. They learned to be hypervigilant, constantly scanning for signs of danger, but had no reliable way to predict or control their caregiver’s responses.

Their developing attachment system is essentially short-circuited. Normal attachment behaviors seeking comfort when distressed became dangerous because the comfort-giver was also the threat. They often appeared dazed, fearful, or showed rapid shifts between different emotional states.

School Age (5-10): Disorganized children often stood out to teachers and other adults as troubled or difficult. They might be aggressive one moment and withdrawn the next, or show concerning behaviors like hurting animals, extreme fearfulness, or developmental regression.

They struggled to form stable friendships because their internal chaos made relationships unpredictable. They might cling to friends desperately, then push them away, or alternate between being controlling and completely passive. Their emotional regulation was severely compromised because they’d never learned coherent strategies for managing distress.

Ages 10-20: Chaos Intensifies

Tweens and Early Teens (10-15): Adolescence is particularly brutal for disorganized teens because the normal identity formation process is complicated by their fundamental confusion about relationships and safety. They often developed what psychologists call “controlling” behaviors becoming either caregiving or punitive toward their own parents.

Some became parentified children, taking care of their unstable caregivers. Others became aggressive or defiant, unconsciously trying to provoke the rejection they expected anyway. Many showed dramatic mood swings, self-harm behaviors, or developed eating disorders as ways to feel some control over their chaotic internal world.

School performance was often erratic, brilliant one day, unable to function the next. Their relationships with peers were intense but unstable, characterized by dramatic friendships that ended in explosive conflicts.

Late Teens (15-20): Disorganized teenagers often engaged in high-risk behaviors substance abuse, dangerous sexual behavior, self-harm, or criminal activity. These behaviors served multiple functions: numbing emotional pain, seeking the chaos that felt familiar, or unconsciously recreating traumatic experiences in an attempt to gain mastery over them.

Romantic relationships became particularly problematic. They desperately craved intimacy but found it terrifying. They might become obsessed with partners, then suddenly withdraw or sabotage the relationship. The closer someone got, the more triggered their fear responses became.

Ages 20-30: The Push-Pull Years

Early Twenties: Disorganized young adults often lived in constant emotional turmoil. They wanted relationships desperately but found them overwhelming. They might have a series of intense, short-lived relationships characterized by dramatic highs and lows.

They often attracted partners who were either similarly chaotic or who were initially drawn to their intensity but became overwhelmed by the emotional volatility. Many disorganized adults unconsciously sought relationships that confirmed their belief that love and pain go together.

Career development was often disrupted by emotional instability. They might show brilliant potential but struggle with consistency, authority relationships, or workplace interpersonal dynamics.

Late Twenties: Some disorganized adults began seeking help during this period, recognizing that their relationship patterns were causing significant life problems. Others became more entrenched in chaotic lifestyles, possibly developing serious mental health issues or addiction problems.

Those who entered therapy often faced a long, difficult process of learning to recognize and regulate their emotional states. The work involved developing basic emotional vocabulary and safety strategies that most people learn in early childhood.

Ages 30-40+: Crisis or Transformation

The Thirties: This decade often represents a turning point for disorganized adults. Either they hit rock bottom and are forced to confront their patterns, or they begin developing what therapists call “earned security” through intensive therapeutic work.

If they become parents, disorganized adults face the terrifying possibility of recreating the chaotic caregiving they experienced. Some become overwhelmed by their children’s needs and inadvertently frighten them. Others become hypervigilant about being perfect parents, which creates its own problems.

However, those who engage in trauma therapy often show remarkable healing capacity. Their early experiences with chaos gave them unusual resilience and empathy for others’ pain.

Midlife and Beyond (40+): Disorganized adults who haven’t addressed their trauma often face increasing life problems, relationship failures, career instability, health issues related to chronic stress, or serious mental health crises.

Those who’ve done the therapeutic work, however, often become incredibly wise and compassionate. Their journey through chaos and back to stability gives them unique insights into healing and resilience. They frequently become therapists, advocates, or helpers themselves.

Many develop what researchers call “coherent narratives” about their experiences; they can tell their stories in ways that make sense and show growth, rather than remaining stuck in chaotic, fragmented memories.

Putting It All Together: Your Attachment Style Roadmap

Now that we’ve explored how the attachment styles develop and manifest throughout life, let’s step back and see the bigger picture. Your attachment style is your starting point. Understanding whether you lean secure, anxious, avoidant, or disorganized gives you the roadmap for creating the relationships you actually want.

The Attachment Style Summary

Secure Attachment (60% of adults): Consistent early caregiving created neural pathways that encode relationships as safe and reliable. These individuals balance intimacy and independence naturally, communicate directly, and handle conflict constructively. They make relationships look effortless because their nervous systems aren’t constantly scanning for threats.

Anxious Attachment (20% of adults): Inconsistent caregiving created hypervigilant threat detection systems. These individuals crave intimacy but fear abandonment, seek constant reassurance, and often overwhelm partners with their intensity. Their emotional sensitivity, when properly channeled, becomes a superpower for deep connection.

Avoidant Attachment (15-20% of adults): Emotionally dismissive caregiving taught these individuals that emotional needs lead to rejection. They value independence, struggle with intimacy, and often appear self-sufficient while secretly feeling isolated. Their emotional regulation skills become assets when balanced with the capacity for vulnerability.

Disorganized Attachment (5-10% of adults): Caregiving that was simultaneously comforting and frightening created chaotic attachment systems. These individuals desperately want connection but find intimacy terrifying, leading to push-pull relationship dynamics. With proper healing, their deep understanding of pain often makes them powerful helpers and healers.

Why This Science Matters for Your Dating Life

When you know the attachment styles, you can:

- Predict your triggers before they sabotage your relationships

- Choose partners who complement rather than trigger your insecurities

- Communicate your needs more effectively instead of expecting people to mind-read

- Break cycles that keep you repeating the same relationship mistakes

- Develop earned security through conscious effort and potentially therapy

What’s Next?

This foundational knowledge of the attachment styles is just the beginning. Each style has its own specific triggers, growth edges, and pathways to healing. Your attachment style influences much more than romantic relationships. Attachment plays a significant role in our friendships, family dynamics, parenting, and even professional relationships. The goal is to understand your behavioral patterns well enough to make informed choices rather than unconscious reactions when someone challenges your emotional security.

Frequently Asked Questions about Attachment Styles

Can attachment styles change over time?

Yes, though they tend to be relatively stable. Attachment patterns remain relatively constant from infancy through adolescence and even into late adulthood, according to studies conducted over periods as long as 59 years. However, corrective relationship experiences, therapy, and conscious effort can create more secure functioning over time.

Do the 4 attachment styles affect all relationships or just romantic ones?

Attachment styles influence all close relationships, including friendships, family relationships, and even professional connections. The patterns are most noticeable in relationships where there’s emotional significance and potential for intimacy.

Is one attachment style better than others?

Secure attachment is considered optimal because it allows for healthy interdependence and emotional regulation. However, insecure styles likely evolved as adaptive strategies for specific caregiving environments. Understanding your style without judgment is more helpful than trying to achieve perfection.

How do I know which of the 4 attachment styles I have?

Professional assessment is most accurate, but you can observe your patterns in close relationships. Do you seek comfort when distressed (secure/anxious) or prefer to handle things alone (avoidant)? Are your relationship needs consistent (secure) or do they feel chaotic (disorganized)?

References: Attachment Styles

Attachment styles and sense of coherence as indicators of treatment adherence and completion among individuals with substance use disorderAspects of Attachment in Relation to Early Maladaptive Schemas in Children Residing in Child Care FacilitiesThe Mediating Role of Early Maladaptive Schemas in the Relationship Between Attachment Styles and Adjustment to Early-Stage Breast Cancer

or