Male loneliness is at epidemic levels. In 2023, 1 in 7 men self-reported that they had no close friends compared to 1 in 10 in 1990. While men are in a decades-long “friendship recession,” women are facing similar challenges. Some research suggests that women may report higher levels of loneliness than men even though they may have more friends. Male loneliness is especially devastating when male suicide rates continue to climb. By 2021, 40% of men with a reported mental illness received mental health care services in the past year, compared with 52% of women, according to the CDC. Years later, loneliness persists and men report decreased utilization of mental health resources according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Male loneliness created a void that was filled by “incels” or the “involuntarily celibate” men who desire women but are unable to connect with them as either sexual or romantic partners. In response to the drought, reactionary manosphere communities developed offering men something they desperately craved: a found family. These groups provide identity and belonging with a twisted sense of purpose. But the support system comes at a devastating cost that deepens isolation, reinforces misogyny, and further alienates men from real, human connection.

The Science Behind Male Loneliness

Traditional male bonding spaces were established at different phases of a man’s life through fraternal organizations, union halls, and even the casual Severance-like workplace friendships. studies indicate a decline in male participation in social groups, with men reporting fewer social ties and less social engagement compared to women, especially in older age. This trend may be attributed to various factors, including shifts in gender roles, a decline in participation in traditionally masculine activities like sports, and changes in the structure of the workplace. (Kannan & Veazie, 2023)

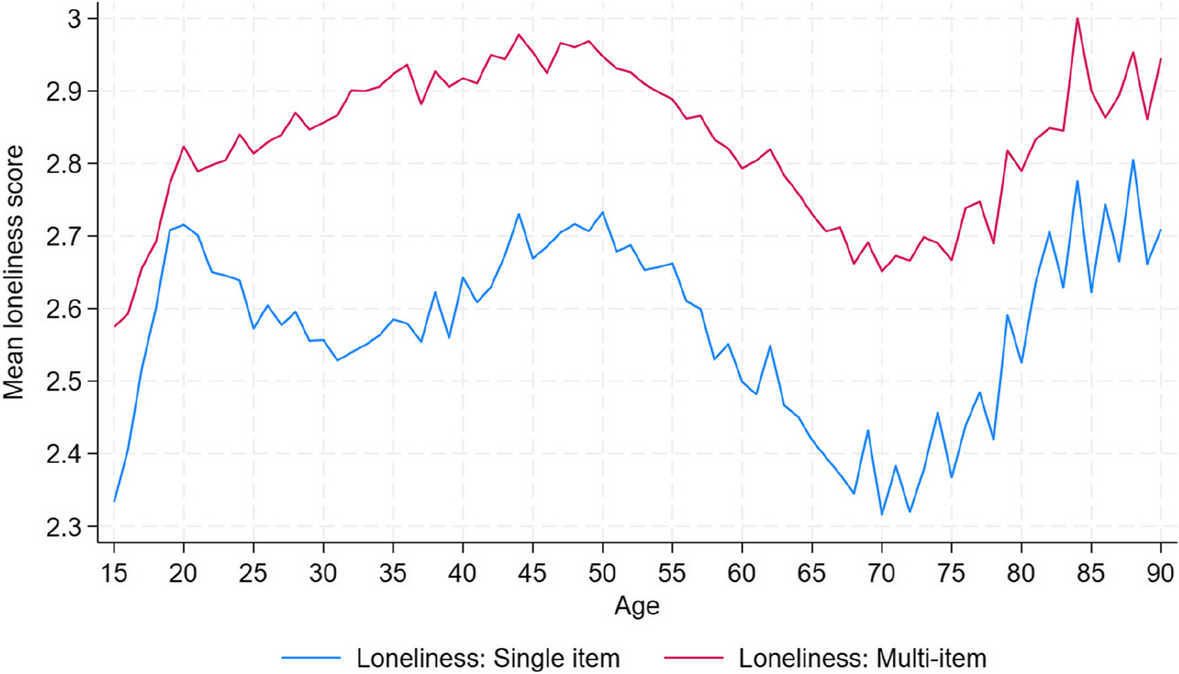

Figure 1 (below) suggests that male loneliness isn’t the lack of social contact but the quality of relationships men build over their lifetime (Botha & Bower, 2024). The study focused on tangible factors that contribute to loneliness like job insecurity, disability, lack of neighborhood ties and lack of supportive friendships. Studies worldwide have shown that men who experience loneliness turn toward online echo chambers where they form parasocial relationships in manosphere or incel communities that deepen their isolation and cynicism (Tietjen & Tirkkonen, 2023). This data suggests that the early-age peak in loneliness for men is during identity formation, while the rise in male loneliness in older age highlights how critical proactive community-building is to emotional survival.

Figure 1. Mean Loneliness Score in Males Between 15-90 Years Old (2002–2022). This line graph shows how loneliness changes across the male lifespan, based on data from over 19 years of the HILDA Survey (Australia). The x-axis represents age (from 15 to 90), and the y-axis shows the average loneliness score (from 1 = low to 7 = high). Two lines are shown: Red Line: Male Loneliness measured using a multi-item scale (detailed assessment); Blue Line: Male Loneliness measured using a single-item question. Both measures show loneliness peaks in late teens to early 20s, dips through middle adulthood, and rises again sharply in older age after 75. The red (multi-item) line remains consistently higher than the blue line, suggesting more sensitivity in multi-dimensional loneliness measures.

Research shows:

- Men are reportedly more dependent on romantic relationships. They turn to their partners for emotional support and intimacy. Women, in reality, are relatively less affected when relationships end compared to men, as they have a strong support system of friends and family to rely on (Wahring et al, 2024)

- Male friendships often revolve around shared activities like sports, work, or gaming, rather than deep, emotionally intimate connections. This tendency stems from societal expectations and how men are often encouraged to express their emotions through actions and shared experiences rather than direct emotional conversations. (Allain, 2022)

- Stigma around vulnerability prevents men from seeking help until they’re in crisis (Sagar-Ouriaghli et al. 2019).

The Incel to Toxic Masculinity Pipeline is a Circle

Male loneliness creates a perfect storm. Humans are wired for belonging, and when real-world connections fail, people turn to digital substitutes. But these spaces operate like Shakespeare’s Claudius, dripping poison into ears under the guise of truth (see actual quote below). Incel forums, “men’s rights” groups, and hyper-misogynistic influencers mimic the structure of community while peddling blame and nihilism. The male podcaster business model depends not on solving male loneliness, but on perpetuating it. It’s akin to certain pharmaceutical strategies that must prioritize lifelong treatment over cures. “Red Pill” podcasters profit from symptoms rather than solutions. Every red pill offered is designed to create dependency on the next dose of outrage.

“Upon my secure hour thy uncle stole;

With juice of cursed hebenon in a vial;

And in the porches of my ears did pour.”

— Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5

How Misogynistic Spaces Mimic Found Family

- Shared Language & Identity: Terms like “Chad,” “Stacy,” and “blackpill” create an insider culture.

- Narrative of Betrayal: Loneliness is framed as women’s fault, society’s fault, rather than a solvable issue.

- Parasocial Bonds: Influencers like Andrew Tate, Sneako, or Fresh & Fit act as surrogate older brothers, offering “hard truths” that blame others for men’s pain.

But this “support” is a trap. These spaces don’t alleviate loneliness—they weaponize it, convincing men that:

- Their suffering is inevitable (the “blackpill”).

- Connection with women is transactional (the “red pill”).

- Any vulnerability is weakness (the “alpha” myth).

Building Real Community

Breaking free requires more than logging off because it demands replacing the toxic parasocial interactions with real connection. As one reader confessed:

“I left the incel forums but still felt empty. Turns out hating women was just my coping mechanism for having no friends. The hard part wasn’t quitting the blackpill. I had to learn how to bond without rage as the glue.”

How to Stop Male Loneliness

Male loneliness is linked to rising suicide rates, emotional isolation, and vulnerability to extremist ideologies. Understanding its roots helps improve mental health, build healthier communities, and reduce harmful social outcomes.

1. Create Male-Centered Emotional Support Spaces

Fund and promote peer-led men’s groups where emotional expression is normalized like hobby clubs or therapist-facilitated groups focused on connection, not competition. Former members of toxic male groups warn: when communities mock vulnerability, obsess over enemies, or reduce self-improvement to dominance, they’re reinforcing isolation.

2. Reframe Help-Seeking as Strength

Launch public campaigns and school-based programs that confront male loneliness head-on. Use real male voices, personal stories, and relatable role models to show that emotional vulnerability and seeking therapy are acts of courage—not weakness. By normalizing emotional expression early, especially for boys and young men, we reduce the stigma that keeps so many suffering in silence.

3. Replace Toxic Online Communities with Healthy Alternatives

Create and join platforms where men can form identity and mentorship without misogyny. Incentivize creators who model healthy masculinity. As one man said, “Told my bro I was lonely. He said ‘Me too.’” That moment rewired his brain. Another shared, “Incel logic says needing help is weak. Reality? Asking was strong.” These communities thrive when emotional honesty is the norm, not the punchline.

Materials: Learn more about our practical tools to reset, reconnect, and stay grounded under pressure: Mental Reset Guide.

The Way Out

Loneliness won’t be solved by blaming women, society, or “weak” men. It’s solved when men dare to connect as human beings. The male loneliness to incel pipeline thrives because it feeds on desperation. But there’s another way to establish a support system with a found family that is built on mutual care and not mutual destruction. The first step is the hardest: logging off, reaching out, and believing something better exists.

Seeking Help

If you or someone you know is struggling with loneliness, mental health challenges, or suicidal thoughts, remember that support is available. No matter where you are.

- In the United States, you can call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988 — free, confidential, and available 24/7.

- In Canada, reach out to Talk Suicide Canada by calling 1-833-456-4566 or texting 45645.

- In the United Kingdom, contact Samaritans at 116 123, available 24/7.

- In Australia, you can reach Lifeline Australia by calling 13 11 14.

- If you are outside these regions, check local mental health crisis lines or organizations. Help is often closer than you think.

References

- Wahring IV, Simpson JA, Van Lange PAM. Romantic Relationships Matter More to Men than to Women. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Published online 2024:1-64. doi:10.1017/S0140525X24001365.

- Allain, K. A. (2023). Masculinity on ice: masculinity, friendships, and sporting relationships in midlife and older adulthood. Journal of Gender Studies, 33(2), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2023.2251903.

- Sagar-Ouriaghli I, Godfrey E, Bridge L, Meade L, Brown JSL. Improving Mental Health Service Utilization Among Men: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Behavior Change Techniques Within Interventions Targeting Help-Seeking. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13(3):1557988319857009. doi:10.1177/1557988319857009