Push-pull dynamics refer to a relational pattern where one or both partners alternate between pursuing closeness (“pull”) and creating emotional or physical distance (“push”). This hot-and-cold cycle is commonly linked to insecure attachment styles, trauma responses, and emotional dysregulation. While sometimes unintentional, the pattern can also reflect power-seeking or manipulative behavior, especially when used to destabilize a partner’s sense of safety or self-worth.

Push-Pull Dynamic

| |

|---|---|

| Category | Conflict, Attachment |

| Key Features | Inconsistency, intermittent affection, emotional volatility, relational anxiety |

| Common Roots | Fearful-avoidant patterns, emotional trauma, attachment injury |

| Typical Behaviors | Pursuing then withdrawing, testing boundaries, creating emotional confusion |

| Common Effects | Hypervigilance, addictive bonding, loss of self-trust |

| Sources: Levy et al. (2018); Psychology Today (2021); APA (2023) | |

Other Names

hot-and-cold relationship, intermittent intimacy, push-pull relationships, push-pull dynamics in relationships, emotional whiplash, trauma bond cycle, anxious-avoidant loop, on-off dynamic, closeness-avoidance cycle, fear-intimacy pattern, approach-avoidant pairing, rollercoaster relationship

History

Attachment Theory and Insecure Pairings

First explored in developmental research, the push-pull dynamic emerged in adult relationship literature alongside attachment theory. Researchers observed patterns where anxious individuals pursued intimacy, while avoidant partners withdrew under pressure. When both tendencies coexist in one partner such as in fearful-avoidant types, the cycle becomes self-reinforcing.

Pop Psychology and Dating Strategy

During the 1990s and 2000s, dating advice books began framing push-pull behaviors as ways to spark attraction or build mystique. Popular media encouraged tactics like playing hard to get, often ignoring the long-term psychological cost. These ideas filtered into pickup artist communities and later influencer culture.

Digital Era and Romantic Chaos Culture

Social media normalized relational drama through storytelling and spectacle. The push-pull cycle, once seen as unhealthy, became aestheticized especially in “situationships,” twin flame content, and online trauma discourse. Many now use the term to describe emotional chaos mistaken for passion or fate.

Biology

Why unpredictability feels addictive

The push-pull dynamic taps into the brain’s reward system through unpredictability. When attention or affection shows up after a period of distance, it creates a “reward prediction error” in which a burst of dopamine is released in response to an unexpected reward. This reaction comes from deep brain regions like the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens, which are sensitive to surprise and emotional payoff. The more unpredictable the closeness, the more intense the reward feels.

How inconsistency trains the brain to chase

Inconsistent “rewards” that you receive like attention, affection, or physical intimacy followed by silence, then followed by affection again create a powerful reinforcement loop. The brain learns to associate emotional uncertainty with potential attention or affection, strengthening the urge to pursue closeness even when the relationship feels unsafe. This pattern mirrors the neurological effects of gambling, where the unpredictability itself becomes exciting and hard to resist.

Why emotional volatility can feel like love

Emotional volatility triggers dopamine release, not just for pleasure, but for novelty and alertness. In push-pull relationships, the back-and-forth intensity creates a chemically charged atmosphere. Over time, the brain becomes sensitized to this rhythm and begins seeking the next emotional high, even if it comes after a crash. This is why drama can start to feel like depth, even when it’s destabilizing.

What your nervous system does during push-pull

Every time someone pulls away or comes back, the nervous system reacts. Withdrawal activates stress responses like cortisol spikes and sympathetic arousal, while reconnection brings momentary calm. These emotional swings are both psychological and physiological. The body gets conditioned to toggle between panic and relief, locking in a loop of craving and confusion.

Why mixed signals make it hard to walk away

Oxytocin, the bonding hormone, is released during both comfort and stress in close relationships. When a partner causes distress and then offers soothing, the brain associates them with both safety and threat. This chemical confusion makes it difficult to trust your gut or exit the relationship, even when it feels unbalanced.

How to interrupt the cycle on a brain level

Breaking the push-pull pattern means retraining both brain and body. Regulation practices, secure connection modeling, and consistent care can help restore emotional clarity. When the nervous system feels safe over time, the brain reduces its craving for unpredictable reward—and starts to recognize consistency as the real form of safety.

Psychology

Attachment-Based Drivers of Push-Pull Behavior

The push-pull dynamic often reflects deep-seated attachment insecurity. Anxiously attached individuals may crave closeness yet become emotionally reactive when their needs aren’t met, while avoidantly attached partners may instinctively create distance in response to perceived intensity. In fearful-avoidant or disorganized attachment styles, both patterns co-occur thus leading one partner to seek intimacy while simultaneously fearing engulfment. This creates an unpredictable emotional rhythm that disrupts trust and regulation.

Distrust, Jealousy, and Escalation of Behavior

When trust is low, the cycle of pursuit and withdrawal can intensify. Research shows that individuals with attachment anxiety are particularly susceptible to escalating cognitive and behavioral jealousy in response to relational uncertainty. In a 2015 study published in the academic-journal Partner Abuse, Rodriguez et al. found that low trust predicts higher psychological reactivity in anxious individuals, including emotional checking, surveillance, and in some cases, verbal aggression. These behaviors reinforce instability, even when the intent is to protect the connection.

Social Isolation, Ambiguity, and Depression Risk

Push-pull dynamics disrupt emotional safety, often leading to internal confusion, disconnection, and symptoms of relational exhaustion. A 2024 umbrella review published in the Journal of Affective Disorders (De Risio et al.) found that social connection is a significant protective factor against depression, while chronic relational instability such as perceived rejection, ambiguity, and emotional withholding can increase vulnerability to depressive symptoms. The dissonance between periods of closeness and withdrawal contributes to emotional fatigue, especially in individuals with limited support outside the relationship.

Emotional Confusion and Intermittent Bonding

The cycle of sudden withdrawal followed by affection can mimic the neural imprint of trauma bonding. The brain’s reward system registers unpredictable emotional cues as high-value, reinforcing pursuit even when safety is compromised. Oxytocin release during brief moments of reconnection can foster false hope, making it harder to exit the cycle. This pattern is often misinterpreted as “chemistry” or “destiny,” especially when reinforced by romantic myths or spiritual ideologies.

Psychopathy, Trauma Symptoms, and Long-Term Effects

In some cases, the push-pull pattern reflects more than insecure attachment. Research from Forth et al. (2021) in the International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology documents how intimate partners of individuals with psychopathic traits report extensive psychological symptoms, including PTSD, dissociation, and chronic depression. When emotional inconsistency is combined with gaslighting, manipulation, or control, the push-pull cycle moves beyond ambivalence and becomes a mechanism of psychological harm.

Recognition, Naming, and Relational Repair

The ability to identify and name the push-pull dynamic is often the first step toward recovery. Therapeutic approaches rooted in attachment repair and emotional regulation can help individuals break the cycle. Building secure self-trust, practicing clear boundaries, and engaging in co-regulation rather than intensity-seeking are essential for sustainable change. While the behavior may stem from fear, healing depends on consistency, emotional accountability, and shared safety.

Sociology

Low-effort dating creates confusion loops

Contemporary dating culture often encourages detachment, vague intentions, and “bare minimum” behaviors. In app-driven environments, direct emotional expression is often discouraged or mocked. When emotional clarity is misread as neediness, people learn to suppress honesty and rely on mixed signals. Behaviors like ghosting, breadcrumbing, and avoidant communication become normalized each laying the foundation for push-pull dynamics that never stabilize.

Gender roles reward Emotional Withholding

Outdated dating advice still teaches many women to act elusive and many men to act detached. “Playing hard to get” is framed as desirable for women, while men are often praised for emotional restraint. These roles reinforce withdrawal as strategy rather than signal. They also blur the line between intimacy and control, making it harder to name real emotional fear beneath the performance of coolness or pursuit.

Spiritual beliefs can mask unhealthy patterns

In spiritual communities, intense emotional chaos is sometimes reframed as a “twin flame journey.” The cycle of rupture and reunion is portrayed as karmic or sacred, even when it causes distress. These beliefs can romanticize volatility, delay accountability, and prevent people from recognizing trauma reenactment. Framing instability as divine purpose often keeps people stuck in cycles of hurt labeled as destiny.

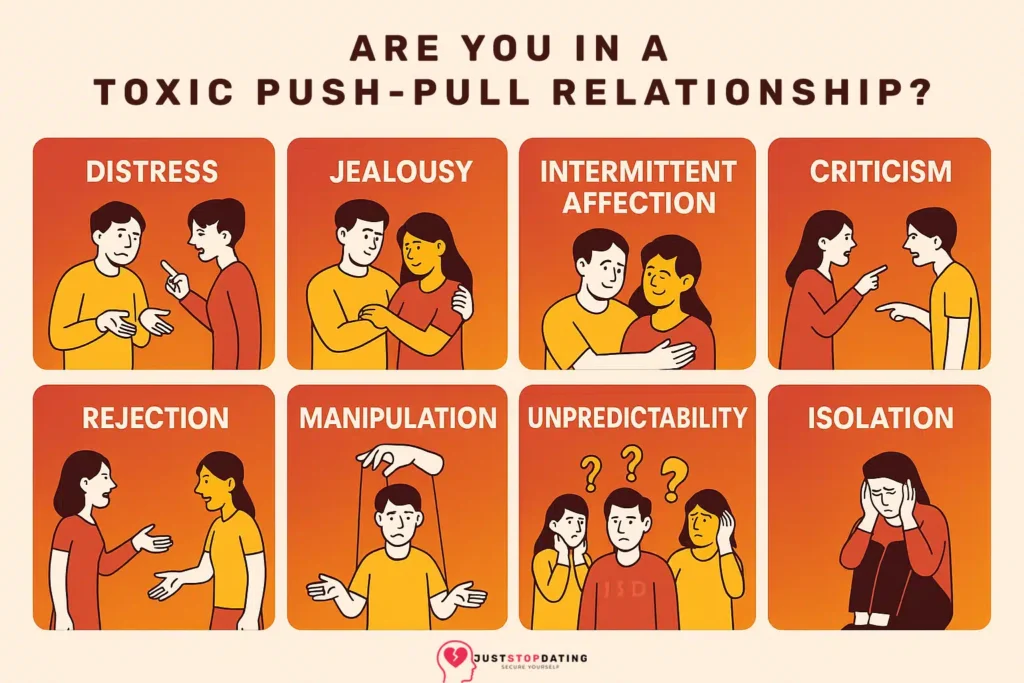

Impact of Push-Pull Dynamic on Relationships

Chronic Insecurity and Anxiety

Partners caught in a push-pull loop often experience anxiety, second-guessing, and hypersensitivity. The absence of consistency creates emotional unpredictability, leading to self-monitoring and exhaustion.

False Repair and Emotional Dependency

The “pull” phase can feel like reconciliation or closeness, but without structural change, the cycle repeats. These highs offer momentary relief but reinforce dependency, eroding emotional safety.

Attachment Injury and Dissociation

Over time, push-pull patterns can lead to emotional shutdown, loss of self-trust, or relational numbness. Some individuals report a collapse in relational confidence, struggling to tell the difference between healthy pacing and familiar chaos.

Key Debates

Is All Push-Pull Toxic?

Short-term distancing in response to stress is common. The difference lies in repetition, predictability, and intent. When the pattern becomes chronic, creates instability, or manipulates emotional safety, it becomes harmful regardless of motive.

Is It Always Attachment-Based?

While rooted in attachment patterns for many, push-pull can also emerge from unprocessed grief, identity confusion, or emotional immaturity. It isn’t always malicious, but its effects still damage trust.

Does the Drama Mean It’s Real?

Intensity and emotional whiplash are sometimes mistaken for passion or cosmic significance. In healthy relationships, security produces depth. Drama can indicate unhealed wounds, not soul connection.

Media Depictions

Film

- Blue Valentine (2010): Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams portray a couple locked in an escalating push-pull cycle rooted in misattuned needs and emotional fear.

- 500 Days of Summer (2009): The relationship dynamic showcases inconsistent intimacy, projection, and emotional mismatch misread as romantic destiny.

- Silver Linings Playbook (2012): Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper navigate trauma and emotional regulation through a dynamic filled with resistance, re-engagement, and eventual co-regulation.

Television Series

- Normal People (2020): Marianne and Connell’s story reflects deeply rooted attachment wounds, shifting roles in pursuit and avoidance, and difficulty maintaining closeness over time.

- Euphoria (2019–): Rue and Jules display chaotic connection, abandonment anxiety, and difficulty with emotional pacing—hallmarks of the push-pull dynamic.

- BoJack Horseman (2014–2020): Numerous character arcs portray relational sabotage, intermittent reinforcement, and emotional inconsistency masked as depth.

Literature

- Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller: Introduces anxious-avoidant traps and explains why intermittent intimacy creates bonding confusion.

- Women Who Love Too Much by Robin Norwood: Explores how push-pull cycles become addictive for individuals drawn to emotionally unavailable partners.

- The Drama of the Gifted Child by Alice Miller: Offers foundational insight into how early emotional deprivation can shape adult emotional volatility and inconsistency.

Visual Art

Contemporary artists such as Tracey Emin and Louise Bourgeois explore intimacy, instability, and longing through recurring imagery of rupture, reconnection, and emotional fragmentation each reflecting the psychological texture of push-pull connection.

Research Landscape

The push-pull dynamic is studied within attachment theory, trauma-informed therapy, behavioral neuroscience, and relationship psychology. Topics include intermittent reinforcement, boundary dysregulation, trauma bonds, and insecure partner pairings.

- Bidirectional regulation factor of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells differentiation: a focus on bone-fat balance in osteoporosis

- Concurrent Viral Transmission and Wildfire Smoke Events Following COVID-19 Pandemic School Closures in New York City: Associations of a Large Natural Experiment With Acute Care for Pediatric Asthma, 2018-2023

- Evaluating the current research landscape in gender-affirming surgery

- What matters most to midwifery clients? Exploring continuity of care preferences through a cross-sectional survey in Ontario, Canada

- Conservative treatment of ameloblastic fibroma a case report with review of literature

FAQs

What is the push-pull rule in a relationship?

The “push-pull” pattern in a relationship refers to a repeated cycle where one partner seeks closeness (pull) while the other creates distance (push). This can alternate between partners or occur within one individual who fears both intimacy and abandonment. The “rule” is not a formal guideline but a behavioral description—often seen in relationships marked by inconsistent emotional availability, unresolved attachment wounds, or poor regulation of closeness and autonomy.

Is a push-pull relationship healthy?

A relationship defined by frequent push-pull cycles is typically unstable and emotionally taxing. While short-term distance or re-engagement can occur in any relationship, persistent patterns of withdrawal followed by pursuit often signal unresolved attachment dynamics or relational misattunement. Long-term emotional safety and mutual regulation are difficult to maintain in this structure, especially when the behavior is unconscious or used to manage power, fear, or control.

What is push and pull in a relationship?

Push and pull describe two opposing emotional behaviors that occur in relationships. “Pull” refers to seeking connection, intimacy, or reassurance. “Push” refers to creating distance, avoiding vulnerability, or emotionally disengaging. When these behaviors cycle unpredictably, they can create confusion, anxiety, and dependency particularly in individuals with insecure attachment patterns. This dynamic can feel intense, but it often prevents emotional stability and trust from forming.

Is push and pull a red flag?

Frequent push-pull behavior can be a red flag when it creates emotional instability, manipulates trust, or prevents clear communication. It becomes especially concerning when used as a control mechanism or when one partner consistently feels anxious, uncertain, or unsafe. While occasional shifts in closeness are part of relational stress, a persistent pattern of push-pull often reflects deeper issues that benefit from therapeutic support or boundary clarification.