Ghosting is the act of abruptly ending communication with someone—typically in a romantic, dating, or social context—without explanation or closure. It involves the complete withdrawal of contact, often via text, phone, or social media, and is characterized by silence rather than confrontation. Ghosting is a common behavior in digital dating culture and is often cited as a form of emotional avoidance or conflict aversion.

Ghosting

| |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Ghosting (Social Withdrawal in Digital Dating) |

| Core Behavior | Unilaterally ending all contact without notice or explanation |

| Primary Medium | Text messaging, dating apps, social media, online platforms |

| Key Traits | Sudden silence, lack of closure, emotional withdrawal |

| Contrasts With | Direct rejection, mutual drifting, slow fade, conscious uncoupling |

| Associated Disciplines | Psychology, digital communication, dating sociology, conflict theory |

| Clinical Relevance | Can trigger rejection sensitivity, abandonment anxiety, or attachment insecurity in recipients |

| Sources: LeFebvre (2017), Psychology Today, Pew Research Center, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships | |

Other Names

Ghosted, ghoster, Silent dumping, digital disappearance, unannounced withdrawal, social fading, emotional vanishing

Mechanism and Typical Contexts

Ghosting occurs most often in casual or early-stage dating, especially on platforms like Tinder, Bumble, or Hinge, where interactions may be brief or transactional. It can happen after a single date, several weeks of texting, or even during long-term dating. The ghoster typically stops replying to messages and may unfollow, block, or otherwise disappear from all digital channels.

Psychological Motivations

Avoidance of Conflict

Ghosters often fear uncomfortable conversations or rejection, opting for silence as a passive way to exit. Many cite a desire to avoid “hurting” the other person—ironically causing more pain through ambiguity.

Low Emotional Investment

In early or app-based interactions, ghosting may stem from viewing the relationship as easily replaceable or lacking emotional significance.

Attachment Styles

Individuals with dismissive-avoidant or fearful-avoidant attachment styles are statistically more likely to ghost, especially when intimacy increases or conflict arises.

Power Asymmetry

Ghosting may serve as a form of micro-rejection, where the ghoster holds emotional power and avoids accountability by vanishing instead of communicating.

Common Examples

- After a first date: One person texts “Had a great time!” and receives no response, ever.

- Mid-conversation: The ghoster vanishes in the middle of planning a second meetup and never replies again.

- Post-hookup: Following a sexual encounter, one party disappears entirely without explanation, leaving the other emotionally confused.

- After weeks of connection: A seemingly engaged person stops texting, unfriends the other on social platforms, and becomes digitally unreachable overnight.

Impact on Ghosters

While the emotional toll of ghosting is typically explored from the perspective of the recipient, emerging research and clinical observation suggest that ghosters themselves may also experience internal consequences. The decision to abruptly sever contact without explanation can reflect short-term avoidance—but may also lead to longer-term emotional discomfort, cognitive dissonance, or relational stagnation.

Emotional Discomfort and Avoidance Fatigue

Although ghosting often begins as an avoidance strategy—used to sidestep awkward conversations or conflict—it may leave the ghoster feeling guilty, anxious, or emotionally unresolved. In some cases, the ghoster remains ambivalent about their decision and experiences post-ghosting anxiety, particularly if they continue to see the person on social media or in shared social circles.

Erosion of Relational Skills

When individuals repeatedly use ghosting as an exit mechanism, they may miss opportunities to build crucial relational competencies: conflict resolution, boundary-setting, and assertive communication. Over time, this avoidance can result in emotional immaturity or underdeveloped interpersonal resilience.

Cognitive Dissonance and Moral Conflict

Ghosters may rationalize their behavior as a form of “kindness” (“I didn’t want to hurt them”), even when the silence is distressing to the recipient. This internal narrative often reflects cognitive dissonance—a psychological tension between one’s actions and values. Individuals who view themselves as kind, empathetic, or emotionally responsible may feel incongruent after ghosting, particularly if the other person had expressed vulnerability.

Relational Karma and Reversal Experiences

Some individuals who have ghosted others report feeling unsettled or regretful when they later become the recipient of ghosting themselves. This reversal can prompt reflection, especially when they recognize parallels in the experience. In therapeutic settings, such moments are often explored as gateways to emotional growth and empathy development.

Dehumanization and Disposability Culture

Digital dating environments often foster a sense of abundance, where people are perceived as interchangeable. Ghosters may internalize this cultural narrative, leading to detachment or objectification of others. Over time, this can erode a sense of relational depth—even outside of romantic contexts—and contribute to feelings of loneliness or superficiality.

Impact on Recipients

Ghosting can produce acute and sometimes lasting psychological effects, particularly for individuals with insecure attachment styles or heightened sensitivity to social rejection. The absence of explanation, coupled with the suddenness of disappearance, disrupts typical emotional processing and can evoke symptoms associated with relational trauma.

Confusion and self-doubt

The unexpected and unexplained nature of ghosting often leads recipients to engage in internal attribution, asking themselves, “Did I do something wrong?” This cognitive dissonance can increase self-criticism and erode relational confidence.

Rejection sensitivity and abandonment triggers

For individuals predisposed to anxious attachment or abandonment trauma, ghosting may activate hypervigilance, emotional dysregulation, or depressive affect. Studies suggest that rejection activates the same neural circuits associated with physical pain (e.g., anterior cingulate cortex).

Inhibited emotional closure and narrative disruption

Because ghosting offers no resolution or explicit ending, recipients are often left with an open psychological loop. This impairs the brain’s natural narrative-completion mechanisms, making it difficult to emotionally integrate the experience or move forward with clarity.

Erosion of relational trust

Ghosting may generalize into broader mistrust in dating contexts, especially in digital spaces. Repeated exposure to ghosting can increase defensiveness, reduce emotional risk-taking, and contribute to cynicism or emotional withdrawal in future connections.

Cultural Normalization of Ghosting

While once considered rude, ghosting has become increasingly normalized in app-based dating, where abundance of options and low accountability environments reduce perceived obligation to explain disinterest. Ghosting reflects broader shifts in communication norms, emotional labor expectations, and online social detachment.

Colloquial Expressions

In modern dating discourse—especially in meme culture, group chats, and online forums—ghosting has given rise to a range of colloquial phrases that capture the emotional absurdity and communication dysfunction it creates. These expressions offer a humorous outlet for shared frustration while reflecting deeper themes of digital disconnection and interpersonal ambiguity.

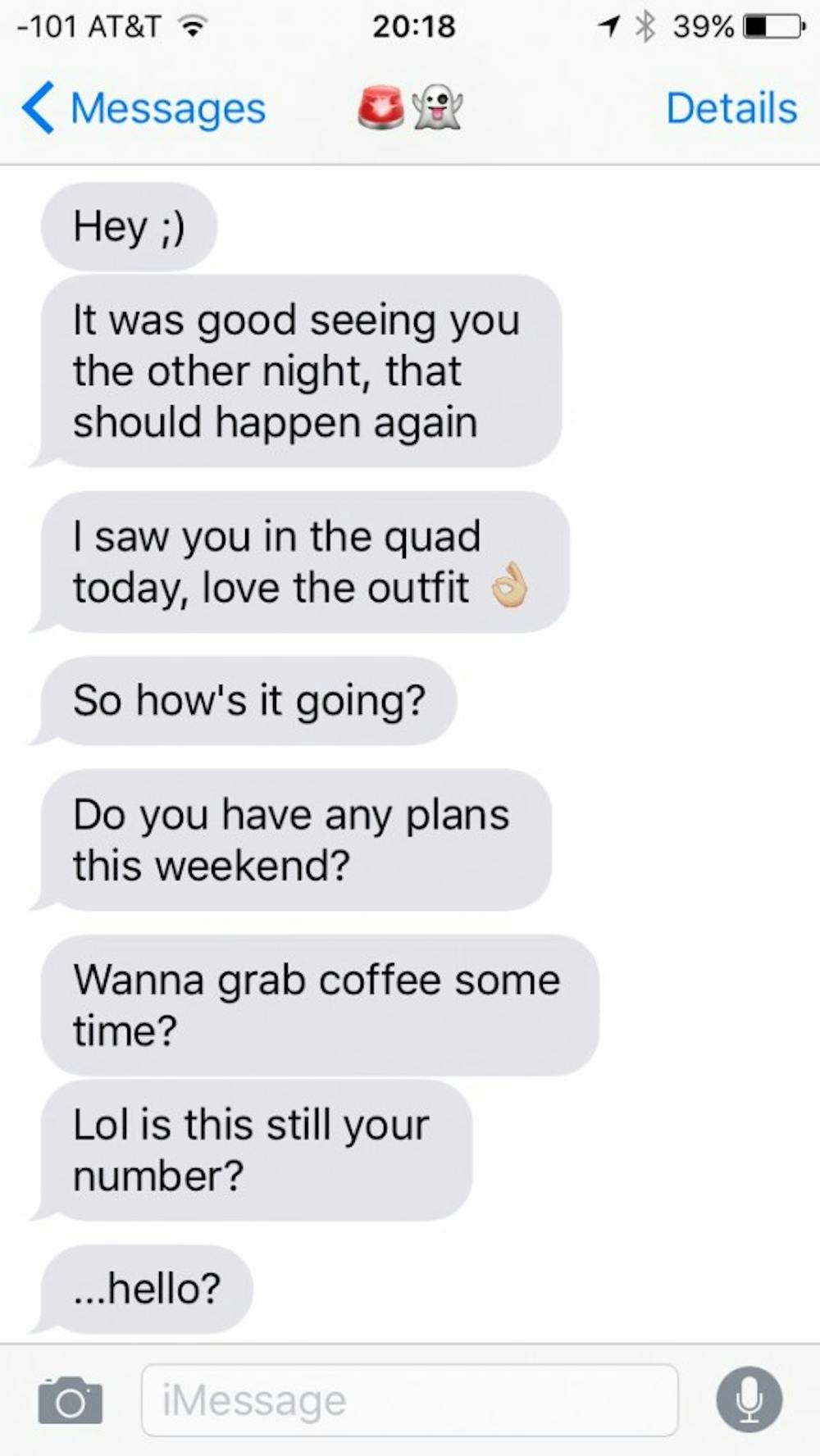

“Talking to Himself in My DMs”

This phrase is used (often by women or femme-identifying individuals) to describe a ghoster who continues to send messages or react to stories after being ignored. Ironically, it can also refer to the reverse: a ghostee who keeps texting long after the other person has gone silent. In both cases, it evokes the image of a one-sided conversation unraveling in real time.

“He’s Having a Whole Conversation by Himself”

Used to describe a situation where one party keeps checking in, texting updates, or sending memes—despite receiving no replies. The phrase often highlights the mismatch in emotional investment and serves as a shorthand for “this person hasn’t taken the hint.”

“Left on Read”

A common expression describing the moment a message is opened and visibly ignored (especially when the app shows a “read” receipt). It symbolizes digital silence and emotional avoidance with an added layer of technological clarity.

“She Houdini’d Me”

A gender-neutral phrase, often used by men, that refers to someone vanishing without a trace after days or weeks of connection. It blends humor with a sense of betrayal—emphasizing how abrupt and inexplicable the disappearance felt.

“Deleted Me Like I Was a Draft Text”

A poetic exaggeration often used for effect in online storytelling. It expresses the sensation of being discarded casually and without warning, as if the connection was always disposable.

These colloquial expressions reflect the deeply human (and often absurd) experience of dating in a digital world. While ghosting may be normalized, the emotional aftershocks are frequently processed through humor, sarcasm, and community storytelling as modern forms of relational meaning-making.

FAQs

Is ghosting ever acceptable?

Some argue ghosting may be acceptable in cases of disrespect, safety concerns, or overt incompatibility. However, communication is generally preferred when safe and feasible.

Why does ghosting hurt so much?

It creates an unresolved psychological narrative, often activating attachment wounds, self-blame, and anxiety. The silence leaves the recipient without explanation or closure.

What’s the difference between ghosting and a mutual fade?

A mutual fade involves both people gradually losing interest and contact. Ghosting is unilateral and abrupt, often following active engagement.

How should you respond to being ghosted?

Avoid chasing or demanding closure from the ghoster. Focus on internal validation, emotional processing, and moving forward. If needed, talk it through with a friend or therapist.