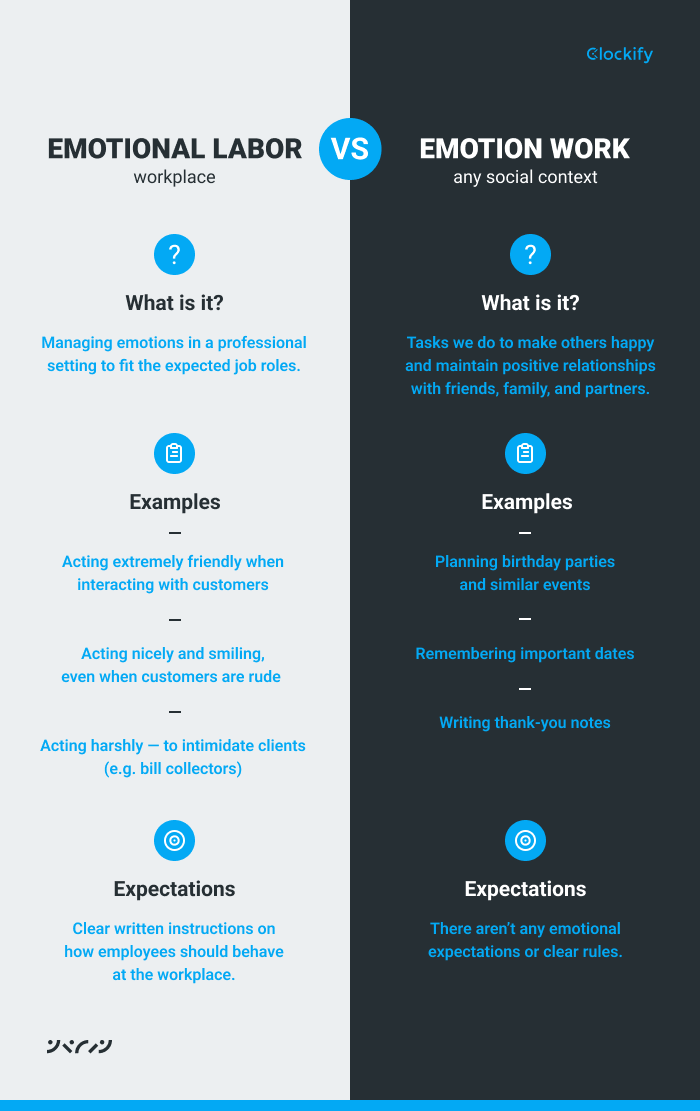

Emotional labor refers to the process of managing emotions, both one’s own and others’, as part of work, caregiving, or relational maintenance. Originally coined in the context of service industries, emotional labor has expanded to include unpaid roles in relationships, friendships, and caregiving where individuals are expected to regulate emotional dynamics to maintain harmony, soothe others, or perform empathy.

Emotional Labor

| |

|---|---|

| Category | Relational Dynamics |

| Related Fields | Sociology, Psychology, Gender Studies |

| Key Constructs | Care work, affect regulation, gendered labor, invisible work |

| Used In | Workplace, caregiving, dating, family systems |

Other Names

affective labor, relational maintenance, invisible labor, emotional regulation work, caregiving burden, unpaid care, social smoothing, empathy performance, emotional caregiving

Historical Context

1970s–1980s: Concept Originates in Labor Studies

Sociologist Arlie Hochschild introduced the term “emotional labor” in her 1983 book The Managed Heart, referring to service workers who must perform friendliness or empathy as part of their job. Flight attendants, nurses, and retail workers were early examples.

1990s–2000s: Expansion to Domestic and Gender Roles

Feminist scholars began applying emotional labor to relationships, motherhood, and caregiving. It became central to critiques of how women and marginalized groups are expected to manage emotional tone without recognition or compensation.

2010s–Present: Cultural Discourse and Online Awareness

Discussions of emotional labor gained traction in public discourse through blogs, social media, and relationship writing. The term was sometimes misapplied to any emotional act but remained vital in analyzing workplace burnout and relational inequality.

Key Debates

Some critics argue that emotional labor is overused and has lost its analytical specificity. Others debate the boundaries between genuine care and coerced emotional performance. In relationships, emotional labor is often gendered, leading to tension around who bears the burden of planning, soothing, or initiating conversations. Questions also arise about whether emotional labor should be redistributed or simply recognized as part of equitable partnership.

Biology

Though primarily sociological, emotional labor engages biological systems such as cortisol regulation, vagal tone, and prefrontal-limbic interaction. Prolonged emotional suppression or empathy overload can trigger fatigue, immune compromise, or dysregulated stress responses. Burnout among caregivers and therapists is often linked to overextended emotional labor.

Psychology

Emotional labor requires self-regulation, empathy, and attentional control. Core mechanisms include cognitive reappraisal (changing how one thinks about a situation) and expressive suppression (concealing felt emotions). In psychological terms, chronic emotional labor without support can reduce well-being and increase symptoms of anxiety, depression, and compassion fatigue.

Sociology

Sociologically, emotional labor is unevenly distributed based on gender, class, and race. Women, BIPOC individuals, and queer caregivers are more likely to be expected to manage emotional climates at home or work. Scholars frame emotional labor as an “invisible economy” that subsidizes social and institutional stability without compensation or acknowledgment.

Relational Accessibility

In dating and relationships, emotional labor often emerges as a patterned imbalance. One partner may routinely initiate repair conversations, absorb emotional outbursts, or manage the couple’s overall emotional climate. Evaluations of online discussions reveal that many women report feeling like unpaid therapists, burdened with invisible work that their partners neither recognize nor reciprocate. In contrast, some men argue that emotional labor is mutual but differently expressed such as absorbing rejection, performing stoicism, or initiating effort in courtship. These differing expectations contribute to dating fatigue and relational burnout, particularly among those with trauma histories or neurodivergence. Awareness of relational access needs including emotional boundaries, reciprocity, and shared responsibility can make dating safer and more sustainable for all participants.

Cultural Impact

Emotional labor has become a flashpoint in modern relationship discourse, often dividing perspectives along gender, generational, and neurodivergent lines. It’s featured in think pieces, therapy language, and social media posts where daters describe being “emotionally exhausted before the second date.” While some reject the concept as an overreach, framing mutual care as a basic human decency, others describe it as the invisible glue holding relationships together. Popular culture has romanticized emotional labor in the “strong woman who fixes him” trope or the emotionally stoic man who finally cracks. These representations obscure the burnout behind the performance. Articles such as “Masculinity and Misogyny Fills the Void” and “Male Loneliness and Incel Hate” explore how unspoken emotional needs can calcify into resentment, avoidance, or toxic scripts. The cultural framing of emotional labor as a duty, gift, or burden who gets supported, who gets stretched thin, and who ultimately opts out of connection.

Media Depictions

Television Series

- Insecure (2016–2021): Explores the emotional load Black women carry in friendships and romance.

- Maid (2021): Centers the emotional and physical labor of a single mother navigating domestic violence and poverty.

Films

- The Devil Wears Prada (2006): Depicts emotional labor in high-pressure work environments.

- Marriage Story (2019): Highlights how emotional labor can become a silent battleground in intimate partnerships.

Literature

- All the Rage by Darcy Lockman (2019): Analyzes the unequal distribution of emotional labor in heterosexual marriages.

- Burnout by Emily and Amelia Nagoski (2019): Connects emotional labor to stress and wellness, particularly among women.

Visual Art

Visual art addressing emotional labor often highlights domestic spheres, bodily burnout, and resistance to invisible roles.

- Conceptual photography of overworked caregivers or “smiling through pain” tropes.

- Installations using everyday household items as metaphors for invisible care.

Research Landscape

Emotional labor is studied in occupational psychology, feminist theory, labor economics, and relationship science. It intersects with burnout, role overload, gender dynamics, and structural inequities in caregiving professions.

- Relationships between nurses' perceived social support, emotional labor, presenteeism, and psychiatric distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional studyPublished: 2025-04-30 Author(s): Hossein Ebrahimi

- The relationship between noise annoyance, emotional labor and burnout in operating-room nurses: A protocol for cross-sectional studyPublished: 2025-04-29 Author(s): Yizhi Zhang

- Editorial: Analysing emotional labor in the service industries: consumer and business perspectives, volume IIPublished: 2025-04-24 Author(s): Weon Sang Yoo

- Well-being and emotional labor for preschool teachers: The mediation of career commitment and the moderation of social supportPublished: 2025-04-24 Author(s): Xiaojie Su

- Empowering leadership and frontline employees' emotional labor: the mediation effects of job passionPublished: 2025-04-23 Author(s): Pengfei Cheng

FAQs

Is emotional labor the same as being kind or empathetic?

No. Emotional labor involves managing others’ emotions as part of a role, often under obligation or pressure. Kindness can be spontaneous, but emotional labor is structured and often expected.

Why is emotional labor often invisible?

Because it does not produce a physical product and is often expected of marginalized people, especially women. It is normalized in both work and relationships as “just being good” or “keeping the peace.”

Is emotional labor bad?

Not inherently. Emotional labor can foster connection and care, but when one person is consistently expected to perform it without support, it becomes unsustainable and unjust.

How does emotional labor show up in dating?

One partner may constantly manage conflict, soothe distress, or maintain emotional connection. When unacknowledged, this leads to resentment and imbalance.

Can emotional labor be shared?

Yes. Healthy relationships involve mutual responsibility for emotional tone, repair, and communication. Shared labor creates deeper trust and reduces burnout.