Male-Male Competition

| |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Male-Male Competition (Intrasexual Selection) |

| Core Characteristics | Aggression, status-seeking, mate-guarding, performance signaling, rival exclusion |

| Developmental Origin | Rooted in Darwin’s theory of sexual selection (1871); expanded through ethology and testosterone-linked behavior research |

| Primary Behaviors | Combat, resource hoarding, displays of strength, social dominance, competitive ornamentation |

| Role in Behavior | Shapes male social hierarchies, risk-taking, and aggressive pursuit of reproductive advantage |

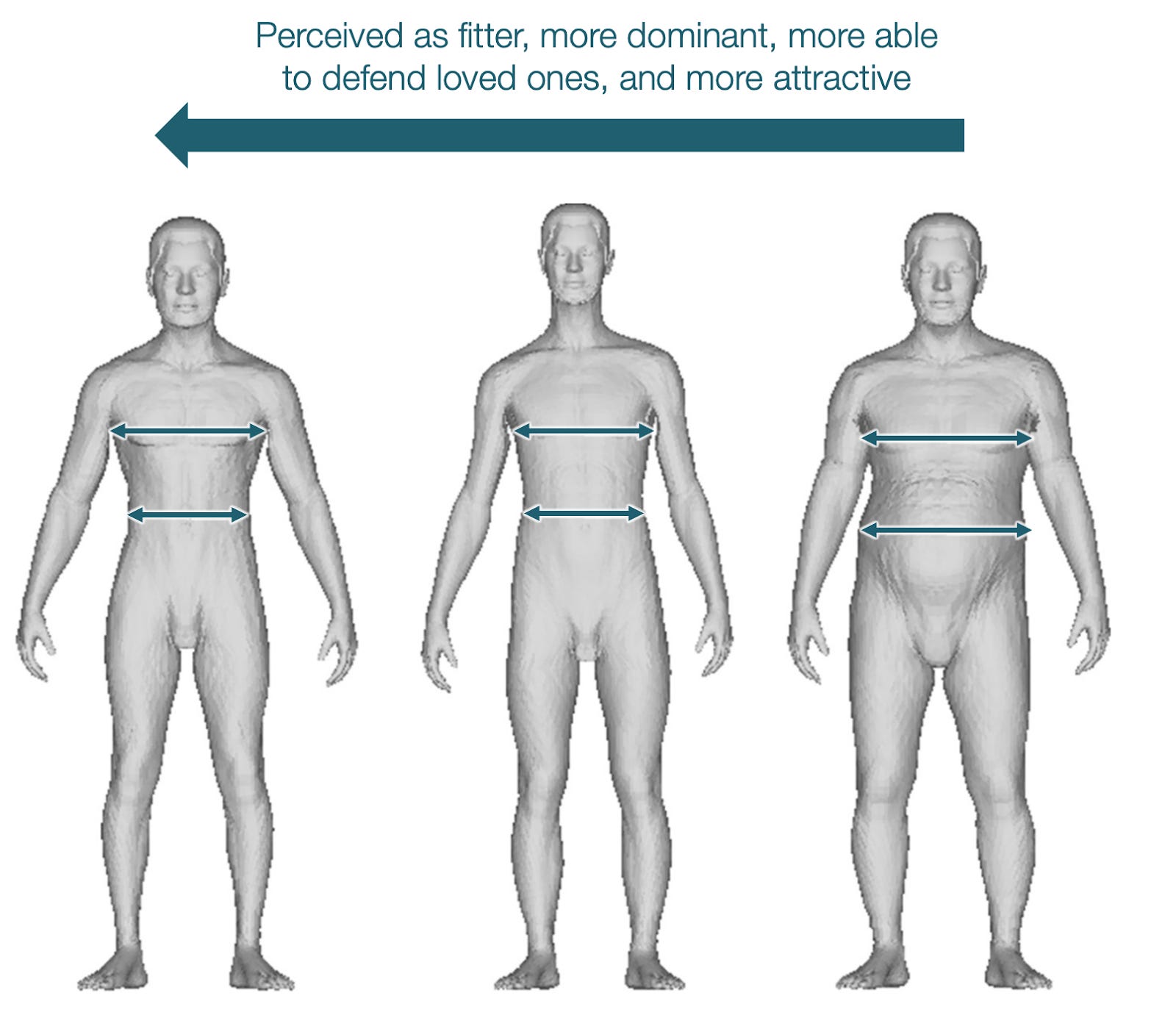

| Associated Traits | Testosterone-driven aggression, muscularity, competitiveness, lowered empathy under rivalry |

| Contrasts With | Female Choice Theory, cooperative mating, mutual selection strategies |

| Associated Disciplines | Evolutionary biology, behavioral ecology, anthropology, neuroendocrinology |

| Clinical Relevance | Informs research on male violence, dominance anxiety, status-driven disorders, and competition-based trauma responses |

| Sources: Darwin (1871), Trivers (1972), Archer (2009), Geary (2010) | |

Other Names

Intrasexual selection, male rivalry, dominance-based mating competition

Definition

Male-Male Competition refers to evolutionary processes in which males directly or indirectly compete with one another for mating opportunities. This may include combat, social exclusion, performance signaling, or monopolization of access to females. It leads to exaggerated traits including physical or behavioral associated with reproductive success.

History of Male-Male Competition

1870s: Darwin’s Dual Model

Charles Darwin introduced sexual selection in The Descent of Man (1871), distinguishing between intrasexual selection (competition among males) and intersexual selection (female choice). He used examples like deer antlers and elephant tusks to explain how male traits evolved for fighting off rivals.

1950s–1970s: Ethological Expansion

Ethologists like Lorenz and Tinbergen observed male displays and aggression patterns in birds, mammals, and fish. Trivers’ Parental Investment Theory (1972) cemented the idea that male-male competition emerges when males invest less in offspring, leading to more intense contest behaviors.

1980s–1990s: Human Applications

Anthropologists and evolutionary psychologists began applying the theory to human hierarchies, showing how male status, wealth, and risk-taking relate to mate access. Buss (1989) linked male competitive behaviors to cross-cultural mating preferences.

2000s: Neuroendocrine Integration

Studies revealed testosterone’s role in rivalry responses and social dominance (Dabbs et al., 2001). Functional imaging confirmed brain activity associated with perceived loss or gain in male status.

2015–2025: Digital and Indirect Competition

Modern research tracks male-male competition through:

- Online dating hierarchies and algorithm-driven status visibility (Fiore et al., 2016)

- Influencer culture and “flex-posting” as status competition (Berman & Frank, 2022)

- Game theory models of non-violent rival deterrence (Wilson & Daly, 2023)

Mechanism

- Testosterone-driven competition: Hormonal surges increase when rivals are present, fueling aggression and mating effort.

- Social dominance cues: Males adjust behavior based on perceived rank and threat level from other males.

- Sex ratio effects: More males than females leads to more intense displays or violence to access limited mates.

Psychology

- Status sensitivity: Male self-worth often tied to perceived dominance or desirability in social groups.

- Rejection sensitivity: Competitor presence heightens emotional volatility and impulsive responses to social rejection.

- Social surveillance: Constant evaluation of rivals in male peer groups reinforces one-upmanship behavior.

- Performance anxiety: Pressure to outshine others may contribute to maladaptive perfectionism in romantic or career arenas.

Neuroscience

- Testosterone modulation: Increases competitive drive and vigilance toward status threat.

- Ventral striatum: Activates during perceived social wins (dominance, attraction, recognition).

- Anterior cingulate cortex: Monitors social conflict and exclusion cues.

- Amygdala hyperreactivity: Triggers defensive aggression during rivalry threats.

Epidemiology

- Observed across nearly all sexually reproducing animals with unequal male reproductive variance.

- In human societies, male homicide rates correlate with mating inequality and competition intensity (Wilson & Daly, 1985).

- Competitive aggression peaks during late adolescence and early adulthood—peak mating years.

Related Constructs to Male-Male Competition

| Construct | Relationship to Male-Male Competition |

|---|---|

| Female Choice Theory | Operates in tandem: while females choose, males compete to be chosen |

| Parental Investment Theory | Explains why males compete more intensely—lower biological cost encourages riskier strategies |

| Dominance Hierarchies | Organize access to mates and resources; arise from repeated male-male competition |

In the Media

Male-Male Competition is a central theme in storytelling across genres. Whether framed as romantic rivalry, social dominance, or performative masculinity, it structures plotlines that reflect evolutionary tension and gender dynamics.

- Film:

- Top Gun – Physical dominance and aerial prowess used to win over love interest and assert status

- The Social Network – Rivalry between male founders centers around power, attention, and recognition

- Gladiator – Literal combat over honor, power, and ancestral legacy

- Television:

- Succession – Male siblings engage in psychological and strategic warfare for control of family legacy and perceived power

- The Bachelorette – Contest format literalizes romantic competition among men for a single female partner

- Literature:

- The Iliad – Agamemnon and Achilles’ conflict rooted in honor and female possession

- American Psycho – Satirical depiction of male status obsession, appearance signaling, and competitive capitalism

Current Research Landscape

Male-Male Competition continues to be explored across disciplines. Current studies examine:

- Hormonal dynamics during digital competition (e.g., esports, dating apps)

- Status anxiety and aggression in economically unequal societies

- Shifts in male mating strategies under low-fertility and high-autonomy conditions

- Socioecological drivers of injuries and aggression in female and male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta)Published: 2025-03-31 Author(s): Melissa A Pavez-Fox

- Intrasexual Selection for Upper Limb Length in Homo sapiensPublished: 2025-02-19 Author(s): Neil R Caton

- Plastic sex-trait modulation by differential gene expression according to social environment in male red deerPublished: 2025-02-18 Author(s): Camilla Broggini

- The role of between-group signaling in the evolution of primate ornamentationPublished: 2024-12-16 Author(s): Cyril C Grueter

- Assessing Variance in Male Reproductive Skew Based on Long-Term Data in Free-Ranging Rhesus MacaquesPublished: 2024-10-22 Author(s): Anja Widdig

FAQs

Is Male-Male Competition only physical?

No. It includes symbolic, verbal, and social forms of rivalry like reputation management, wealth signaling, or career performance.

Is this theory relevant in modern, egalitarian societies?

Yes. Even in modern contexts, status-seeking and competition for attention or resources persist, though often in subtler or digital forms.

Is Male-Male Competition the same as toxic masculinity?

No. The theory is neutral and descriptive; “toxic masculinity” refers to harmful social norms. Competition itself is neither inherently good nor bad.

Can women engage in similar competition?

Yes, though it often takes different forms like indirect aggression, social manipulation. Intrasexual competition exists across sexes but manifests differently.